Komatsu (6301, KMTUY)

Bargain industrial with exposure to the resources upcycle

Note: This article was originally written on November 6, 2022

Industrials have been quite resilient this year. Their stocks prices have run up as sector earnings fared better-than-expected, and as investors have looked for safety under the cover of ‘real economy’ stocks during a year in which tech is down big.

You may think that the train has left the station already with blue chip industrials like Caterpillar and Deere. They’re certainly trading near all time highs! But hold on. There is one train which hasn’t left yet, and that is Komatsu. Investors can own one of the great global mining and construction equipment franchises for just 9x P/E and a 4.3% dividend yield. The company also has excellent management team and is conservatively capitalized (also a weak yen beneficiary).

Growth will come from the mining equipment business which sits at an inflection with strong drivers - both structural and cyclical - for upside. In this report, we will walk you through the backdrop of mining equipment demand and why we believe Komatsu is strongly positioned to capture upside. In today’s world, being able to benefit from a resources upcycle is a desirable characteristic and hedge for any portfolio. At the same time, supported by a low multiple and resilient earnings from the aftermarkets business, we feel the downside for the stock is limited.

Komatsu is also a technological leader, and there are some extremely exciting innovations going on in the field including autonomous mining and intelligent construction leveraging data, which we will also discuss. Whether you are a value, growth, or even tech investor, we believe there should be something of interest here.

The mining equipment upcycle

The world is entering a new resources supercycle as the transition to alternative energy requires tremendous increase in mining activities.

A single EV battery weighing 1,000 pounds requires extracting and processing some estimated 500,000 pounds of materials from Earth. For example, lithium brines contain less than 0.1% lithium, meaning to get to 25 pounds of pure lithium (that is the amount typically required for a battery) it requires extracting 25,000 pounds of brines. Repeat this with cobalt, nickel, graphite, and copper, and also factor in the overburden removal that has to be done before being able to reach these ores in the first place. You start to see how resource intensive de-carbonization really is.

IEA has estimated that in order to meet the 2030 de-carbonization targets the world will require 60 more nickel mines and 50 more lithium mines among others (below). The world is running into structural shortages across almost every single de-carbonization metal, and this will only get worse if investments do not keep up.

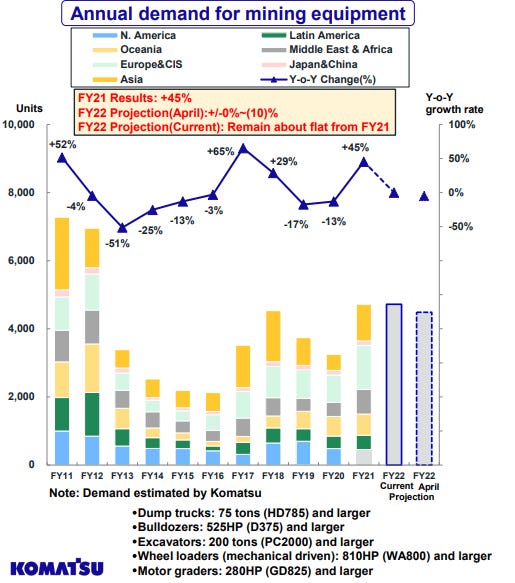

Although the growing need for resources is clear, investments have fallen behind. The commodities crash of 2012 resulted in a decade of slump. Faced with low commodities prices and growing backlash related to ESG, miners have curtailed investments, and have instead focused on cost cutting and debt reduction for the past decade. For mining equipment makers (which we will call OEMs from now) this was the song of death. As shown below, equipment demand was down 70-80% from the peak.

Since bottoming in 2016-17, equipment demand has recovered in recent years. But we still think this equipment upcycle has legs, and here we will examine this from several different angles.

Following the commodities crash, one thing the miners did to try to reduce spending was to delay replacing their fleets for as long as possible. As a result, the average age of equipment in the field has been pushed up over the years. Rather than ordering expensive new equipment, miners turned to OEMs to help them extend the useful lives of older equipment, through programs such as remanufacturing and rebuilds. One industry expert describes the situation as follows:

“What's interesting is when we went through the commodity downturn when all the mining companies had such difficult troubles and all the CEOs of the mining companies got fired after 2012, the CapEx budgets for all these mining companies just got decimated. A lot of these mining companies working with the OEMs came up with ways to extend the lives of a lot of this equipment. You've been able to now see equipment that typically would be worn out after five, six, and seven years. Now then, 10, 12, and sometimes over 15 years. There's some equipment now up in the oil sands up in Canada that have over 125,000 hours on them that were delivered in 1999.”

- former MD of Surface Mining at CAT (Jan 2021, Stream Transcript)

Typically, mining equipment are manufactured with the intent of operating for 80,000 hours. Assuming 22 hours per day of use on average, this is 10 years of operation. It is possible to keep using the equipment long after this, but this comes at a cost of increase in equipment downtime (breakdowns and repairs), which reduces productivity and compromises mine safety. In this sense it’s actually not so different from a used car.

“My personal opinion is that there is some pent-up that needs to be done. If you don't spend CapEx on a regular basis for replacement, you are just kicking the can down the road. If you pull the strings and don't spend, that means you need to spend more later, providing that your operations are still operating.

– Former VP Epiroc (Aug 2022, Stream Transcript)

When you look at the industry, a significant amount of equipment was purchased during the upcycle from 2010-2012. These equipment are coming to be 10-12 years old, which is when they typically enter the replacement phase.

The Parker Bay Company, which is a specialist consulting firm in mining, estimates the current global population of active equipment to be roughly 80k for five major classes of surface equipment (dump truck, bulldozer, excavator, wheel loader, motor grader). Referring back to our previous chart, for many years equipment demand was below 4k per year, and at the trough reached as little as just 2k. Only last year, demand reached 5k. At 5k, it will take 16 years on average to replace the current equipment population. Optimistically, replacement should be 10 years (= 8k annual demand), which means the range from 5 to 8k would be one way to think about the upside. This assumes constant resource production. But as we know, production volume grows every year which means upside should be greater, and possibly much greater, as cycles tend to overshoot in this business (in either direction).

We can break up the pent-up demand into two areas: brownfield and greenfield.

Brownfield: replacement of an aging equipment population, which has been delayed by the weak commodities environment prior to 2020 and then Covid-related bottlenecks since 2020. To increase brownfield production, miners have to increase utilization (e.g. global copper mine utilization is 84%). This leads to increase in sales of equipment, parts, and servicing for OEMs.

Greenfield: This is basically an optionality which is more dependent on commodity prices. Because it takes time for new mines to come online (several years to decade or more), this will not bring immediate sales, but an increase in backlog should nonetheless help share price in anticipation for higher future earnings.

A major structural tailwind is the decline in mine ore grades globally. For example, copper mined today typically contains only 1% or less copper content, compared to 150 years ago when ore grades were more than 5% and even as high as 10%. Silver is illustrated below – since 2005 the grades of mined silver ore have declined by 55%. This means more material has to be dug out to ensure consistent metal output, which bodes well for equipment makers as the usage intensity of equipment increases over time. This is especially the case for haulage (trucks) as you need more trips to maintain the same amount of metal output.

Another important distinction to understand is surface versus underground. The easiest-to-reach mines are on the surfaces of the Earth. As many surface mines have already been exploited, mining is increasingly moving underground. Mines can either start as underground mines from the very beginning, or surface mines can eventually be depleted to the point that it becomes an underground mine. This doesn’t mean surface mining will be gone anytime soon. On an absolute basis it is still expected to grow but underground will be growing faster and will account for a higher share of incremental resources mined. This is shown below.

Underground mining can be grouped into soft rock (mostly coal but also salt, oil shale, potash, and others) and hard rock (copper, nickel, tin, iron, silver, gold, and others). Coal accounts for the majority of soft rock mining so it isn’t a particularly attractive area for growth. On the other hand, hard rock deals with all the electrification metals and this is really the place to be for mining equipment makers today.

It’s important to note that the mining equipment used is completely different between surface and underground (this is easy to see), but even within underground, equipment is different between soft and hard rock. The split between the equipment market size of surface vs. underground is roughly 2:1. Within underground, the split between soft rock and hard rock is again roughly 2:1. However, underground hard rock is growing faster than the rest, and certainly at some point in the future (a decade, two decades from now) it will overtake soft rock.

Komatsu and CAT are dominant in surface mining equipment, while Scandinavian players Epiroc and Sandvik are dominant in underground. Komatsu and CAT have been pushing more into underground for obvious reason that they also want to participate in this growth segment. But it’s not easy to compete with the Scandinavian companies which have a long history of dominance. We will come back to this later.

All things considered, mining equipment is a growing industry. The above chart (source: Precedence Research) is forecasting 11% CAGR for mining equipment to 2030. This includes underground equipment which is expected to CAGR at 15.3%. This is certainly a higher growth estimate than what the industry is used to seeing in the past. But we don’t think this is particularly aggressive, for an industry with both structural and cyclical drivers as we highlighted, and even more so if we assume the high rates of inflation today will be rather sticky and persist in the mid-to-high single digit range during the forecasting period.

We are in midst of a resources upcycle, and we think equipment OEMs are a good way to gain exposure. Komatsu has strong balance sheet (debt-free if excluding the financing book for construction equipment, and for the latter the risk is low). The company also has very high aftermarket revenue (65% of mining sales is from aftermarket and 48% on a consolidated basis). As long as resource production remains steady, downside is limited, while investors have the optionality of resources upcycle. Lastly, what we like about equipment makers is that they don’t have the same kind of direct political and legal/policy risks that miners have to face. Politicians and environmentalists don’t go after the equipment companies and that makes a difference.

As shown below, Komatsu’s quarterly sales of mining equipment has been a straight line up since the pandemic. We think there is still more room to grow. Next, we take an in-depth look at Komatsu’s businesses.

Komatsu

Komatsu is the world’s second largest maker of construction and mining equipment, after Caterpillar. Revenue split is roughly 60:40 for construction and mining equipment. But because of the higher contribution of aftermarket revenue in mining (65%) compared to construction (36%), we believe that mining is the bigger contributor to the company’s bottom line. When we combine mining and construction, the company gets 48% of revenue from aftermarket.

Komatsu’s origins date back to 1917 when a mining company called Takeuchi Mining established a subsidiary for making its own copper mining equipment in-house. This subsidiary became independent in 1921, becoming Komatsu. Komatsu is known as one of the earliest Japanese companies to expand into international markets, having done so as early as 1950’s and 60’s (which was around the same time as most Japanese automakers). Just like Japanese automakers in the early days, at first Komatsu was regarded as a low quality knockoff in Western markets. However, in the 1960’s the company benchmarked itself against Caterpillar and took on major quality improvement initiatives. With Japanese ingenuity, it didn’t take long before Komatsu reached parity with Caterpillar for quality. Today, Komatsu competes neck to neck with Caterpillar across the entire mining and construction product lineup, and is regarded as one of the top brands synonymous with quality production and industry leading technology.

Mining equipment business

For surface mining equipment, the market is basically a toss-up between Komatsu and Caterpillar, which are the only two global players capable of supplying a full line of surface equipment (dump trucks, excavators, shovels, and wheel loaders of all specs and sizes).

“I would say that Caterpillar and Komatsu fight for probably 80% of the business amongst themselves and the 20% remaining goes to Hitachi and Liebherr primarily.”

- former MD of Surface Mining at CAT (Jan 2021, Stream Transcript)

Any discussion of Komatsu’s mining business would have to start with a mention of its acquisition of Joy Global in 2016. Joy was a global manufacturer (headquartered in Milwaukee) of both surface and underground mining equipment, operating under the ‘Joy’ and ‘P&H’ brands. This was a sizable purchase for Komatsu, and importantly, one which we believe was a very good capital allocation from both a strategic and financial angle.

Strategically, the acquisition accomplished two things. First, it expanded Komatsu’s surface equipment lineup and has done so in a highly complementary way. Komatsu has always had a very strong lineup of dump trucks and hydraulic excavators. Joy was well-known for its ultra large extraction/excavation equipment including draglines, rope shovels, and ultra large wheel loaders. Below is an illustration showing just how large Joy’s equipment are (placed next to Komatsu’s largest mining excavator PC8000 which is to the most left side of the diagram). Komatsu was previously missing these equipment, and after adding Joy’s lineup, Komatsu became a full line supplier capable of competing against Caterpillar across the entire surface mining spectrum.

Second, Joy’s sales split was 50/50 between surface mining and underground. The acquisition gave Komatsu its first foray into underground equipment.

As you can see below, the acquisition has expanded Komatsu’s storefront significantly.

The acquisition also demonstrated Komatsu’s financial astuteness. Komatsu took advantage of a depressed mining market in 2016, buying out Joy at an equity value of only $2.9bn or $28.3 per share (Joy’s stock traded at over $90 at the market peak). The acquisition multiple was less than 1x LTM revenue (with 76% Joy’s revenue in aftermarket sales) and 10x (depressed) cash flow. It’s interesting to point out that Caterpillar’s acquisition of Bucyrus in 2010 has many strategic parallels to this one, but CAT overpaid for Bucyrus at the market peak – paying $8bn (at 2.5x revenue and 16x EBITDA, keep in mind these were on peak numbers). The capital allocation award definitely goes to Komatsu.

While Komatsu is a leading player in surface mining, its position in underground is a lot weaker. Despite having acquired Joy’s underground portfolio, the problem is that Joy’s products are mostly for soft rock mining, 90% of which is for coal. As we noted earlier, underground hard rock is the place to be, and in this segment Komatsu is still a very small player. This niche is dominated by two extremely strong Scandinavian players – Epiroc (spun off from Atlas Copco) and Sandvik which have roughly a third of the market share each in underground. Komatsu has positioned its underground hard rock division as a priority business, aiming to reach a sales of US$300mn by 2024 (~three times the company’s sales this year). However, even at $300mn this is a tiny fraction of the Scandinavian players which have $4bn of revenue each.

Komatsu’s resources exposure is shown below. Total coal exposure is 34%. Thermal coal (used for electricity generation) exposure has been reduced from 35% down to 24%. Coking coal has remained steady at 10% (used for steelmaking and is proportional to steel demand). Copper and others have grown in proportion. Directionally this is healthy. It’s worth noting that while thermal coal is purportedly in decline, its demise seems to be exaggerated. Production will likely continue to remain resilient thanks to the increase in production by India and other emerging markets - this is shown in the second diagram.

The mining equipment industry operates under a slowly consolidating global oligopoly. Sales of mining equipment often takes on a direct sales model, and OEMs have close and long-term relationships with miners. It’s worth expanding on this.

Mining equipment is not a simple ‘hardware’ business. It’s a solution based business to help miners reduce TCO (total cost of ownership). In recent years ESG has also become increasingly important for miners, and OEMs have jumped on this opportunity. For example, OEMs have successfully used technology such as automation to help miners achieve higher mine safety and reduce emissions - we will expand on this later.

Aftermarket is key to what makes this a great business. OEMs will sell a dump truck and secure virtually guaranteed profit over the next 10+ years from highly profitable aftermarket sales as these machines work 20+ hours per day in the mines under harsh conditions.

The scope of aftersales support can differ greatly by customers. All customers would be purchasing parts, but some choose to service their fleets in-house, while others would sign long-term servicing contracts with OEMs who will help take care of every aspect of fleet maintenance and servicing. This can include even the warehousing of parts inventory for these customers. These can be very big multi-year contracts that span the entire life of an equipment (10 years).

Every minute that the equipment is down represents lost revenue for miners. Minimizing equipment downtime is crucial. As one purchasing manager told me, what OEMs are selling is really the brand of assurance and the reputation for strong support.

“The remote locations where a lot of these mines actually work provides some very, very unique logistics challenges. Being able to cope with that and have the reliable infrastructure in place to do that goes right back to the amount of time the machines can actually run efficiently and on time to keep materials flowing to the processing plant.”

- former MD of Surface Mining at CAT (Jan 2021, Stream Transcript)

It’s also worth mentioning that regional distributors can play an important role in certain markets. For example, United Tractors (part of the Jardine Matheson conglomerate) is the exclusive distributor of Komatsu equipment in Indonesia. It has a massive distribution and servicing asset footprint in the country which includes dozens of workshops and remanufacturing facilities, and over a hundred warehouses and distribution centers. Given the unique challenges such as logistics and securing trained technicians in a market like Indonesia, it makes sense as to why Komatsu may rely on this partner to a great extent. OEMs can be selective in where they want to put up their own capital to serve customers directly, versus letting distributors do it.

The other really important piece to understand is technology. Most people might not associate mining operations with a lot of technology, but this is an increasingly important piece for investors to understand (everyone talks about autonomous driving these days, but few people talk about autonomous mining!) A decade of low commodity prices have cut miner spending, but technology has been the one area where they have shown willingness to invest. This is because the returns are clear. Technology not only allows miners to bring down their cost of operation, but also helps them to achieve decarbonization goals.

“To achieve our decarbonization ambitions, Rio Tinto is working with key partners like Komatsu”

–Chief Commercial Officer, Rio Tinto

The biggest advancements are happening in automation. Komatsu has actually been a pioneer in this field, having started its first research in autonomous mining trucks in 1990, and was the first OEM to commercialize autonomous mining trucks in 2008 starting in Chile, then expanding to Australia, Canada, and Brazil. Since then Komatsu has been at the forefront and now has 400 autonomous trucks running at 13 sites in four countries.

Miners are pursuing automation for mine safety and productivity reasons. Personnel shortages, rising wages, worker strikes, worksite injuries/deaths – these are all major headaches for miners and reasons why miners want to achieve automation. As shown below, mining and construction have the highest number of fatalities out of all industries.

Automation also leads to lower cost of operation and emissions savings. Computers are better and more efficient drivers than human operators. According to Komatsu, autonomous fleet can be 15% more productive, and average 40% improvement in tire and brake life leading to 13% reduction in maintenance spending. Computers can also gather data on the entire mine operation, optimizing for not just each piece of equipment but the efficiency of the whole system (e.g. reducing truck downtime)

OEMs capture value from technology in two ways. First, it leads to higher selling price. Second, software is a major part of the business. Automation makes it difficult to run mixed fleets but Komatsu offers an interoperable software which the company is now trying to develop into an industry standard for autonomous mining. As technology progresses, smaller OEMs tends to get left behind, finding it hard to keep pace with the required spending on technology. This could further lead to industry consolidation down the line.

Other than automation, Komatsu’s other technology initiatives include developing trucks that run on alternative power sources including hydrogen and battery.

As an aside, we were surprised to find out that Cathie Wood owns Komatsu in the ARKQ fund (ARK Autonomous Technologies and Robotics ETF) as the fund’s 9th largest position. Investors may have widely varying views on Cathie. But we do think it’s noteworthy, at least as far as technology is concerned, that a fund whose mantra is ‘innovation’ owns a company seemingly so traditional as Komatsu. Another observation is that ARK also owns Caterpillar, but Komatsu is the larger position between the two.

Construction equipment business

Komatsu has sales footprint across the globe, but its construction equipment business can be thought of as mostly a developed market business, with a large exposure to North America. Geographic sales breakdown provided by Komatsu (below) doesn’t distinguish between mining and construction. But once we strip out the major mining regions of Latin America, Oceania, and some parts of Asia (e.g. Indonesia), you can clearly see the remaining exposure is heavily concentrated in mainly North America, Japan, and Europe.

Unlike mining equipment which is a global oligopoly, construction equipment is much more fragmented. The largest three players Caterpillar, Komatsu, and Deere only have 40% market share in North America, and there is a long tail of other brands – Volvo, Hitachi, Kobelco, Hyundai, Doosan, Liebherr etc. Customer base is fragmented and therefore construction equipment relies on dealerships to a great extent for its sales and servicing network. Dealerships are typically independently owned, although some OEMs including Komatsu utilizes a mix of corporate-owned and third party dealerships.

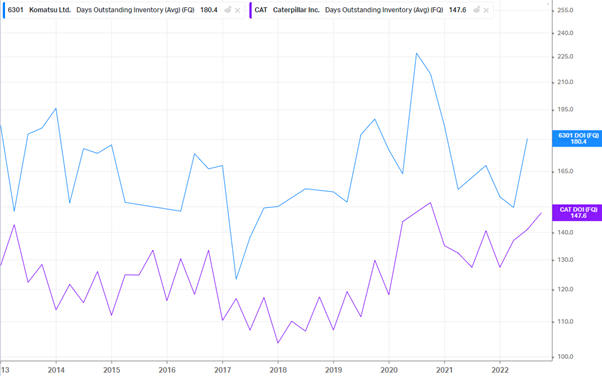

A dense network of well-capitalized dealerships is the biggest moat that an OEM can have in this business. When it comes to this, Caterpillar is by far the leader in North America. Construction is a cyclical business, and most OEMs have to provide plenty of working capital support for their dealers. After 2008 the construction industry struggled greatly and during this time Komatsu introduced a “zero inventory” policy for its dealers i.e. Komatsu helped dealerships carry inventory on its book. It’s worth noting that Caterpillar consistently boasts the best working capital numbers in the industry, and the key reason for this being the financial strength of its dealers which does not require Caterpillar to offer significant working capital support. This results in better cash conversion for Caterpillar which we believe is one justification for Caterpillar’s premium valuation over Komatsu.

Technology also plays an important role in the construction equipment business and Komatsu has also been a pioneer here. In 1998 Komatsu rolled out ‘Komtrax’ which tracks equipment location and gathers various equipment operating data (fuel consumption, operating time, etc.) Since 2001, every piece of construction equipment which Komatsu sold has Komtrax equipped as a standard feature.

With Komtrax, Komatsu has visibility into the utilization of its equipment across the world. With this, Komatsu is able to better forecast equipment demand to optimize its production schedule and equipment inventory. Accurate demand forecasting has been a key enabler for the zero inventory policy earlier discussed. In addition, the company can also forecast the maintenance schedule for equipment and place aftermarket parts where it is needed at the right time.

Komatsu has been gathering and tracking field data for over 20 years. Construction remains one of the few work sites where digitization has yet to truly take hold. Over the years, Komatsu has tried to turn its digital know-hows into business opportunities. For example, the SMARTCONSTRUCTION software platform was launched in 2015. Komatsu calls this the digital transformation of the construction site, integrating real-time equipment data, aerial mapping, and other geographic data to provide real-time visualization of the construction site. Komatsu has also developed ‘intelligent control’ equipment which can perform precision work (bulldozing and excavation) based on terrain data. This is illustrated below – in the first picture, the computer adjusts the bucket angle. The result is shown in the second picture. The key advantage of this is that even amateur operators can get the job done (as good as veterans with decades of construction experience). In a world with shortage of construction workers, technology is playing a bigger and bigger role.

Retail financing is another key piece of the construction equipment business. Most of Komatsu’s financing assets are in North America, and the division has maintained a conservative capitalization of roughly 3.5x net debt to equity ratio. The risk of customer delinquency is mitigated by Komtrax which allows Komatsu to track the location of customer equipment for repossession (Komatsu can even lock the engine so that it’s inoperable in the case of delinquency). The high resale value of Komatsu equipment also mitigates the risk, as repossessed equipment retains its value well.

Management

We believe Komatsu’s management is excellent. Although Japanese companies are often regarded as having worse management than their Western counterparts, Komatsu is an exception to this.

Capital allocation: As demonstrated by the Joy Global acquisition, management has proven value-conscious and counter-cyclical its approach to capital allocation. This is exceedingly rare (even more so for Japanese management!)

Komatsu seems to have a healthy system and culture for management succession planning. In the past, older Chairman and CEOs have always vacated their seats in time for the younger generation of managers to move up (current CEO is 61 and Chairman is 68). This is often not the case in a seniority-obsessed Japan, where executives have the tendency to stay in their top jobs well past what should be retirement age (to the detriment of younger workforce and also shareholders)

Komatsu benchmarks itself against global peers and aspires to be the best in industry - for example, KPIs include “growth rate above industry average” and “industry’s top-level operation income ratio”.

Good shareholder returns: management has committed to a consolidated payout ratio of 40% or higher.

I have met with the company around seven or eight times over my career. My impression of management is that they are long-term focused, strive to be good corporate citizens, while having a healthy amount of respect for the capital markets and minority shareholders.

Financials and Valuation

If the mining upcycle continues, then operating margin and ROE have potential to reach mid- or even high-teens (provided also yen doesn’t appreciate significantly). But I think it’s reasonable to assume on average this will be a low-teens ROE business over a cycle.

Komatsu is a beneficiary of a weak yen. But keep in mind a lot of production is done outside of Japan, so the FX benefit isn’t as significant as some other Japanese manufacturers with high ratio of domestic production (e.g. Fanuc). Below, we can see that roughly a third of sales comes from “domestic production, overseas sales” which is the portion that benefits most from yen depreciation.

Komatsu’s capex has been in the range of 160-180bn yen in the last few years. It’s worth noting that out of this, production facilities only account for about 70-80bn, with the rest being equipment for leasing and rental. The latter creates delay in cash flow as payments for leasing and rental is spread out over a few years following equipment delivery.

When the economy is good, Komatsu invests substantially in leasing and rental equipment, and also builds up working capital as it has to hold increasing inventory for dealers. Therefore during upcycle, cash conversion suffers greatly (FCF was almost zero in FY17/18). But in a downturn all of this works in reverse and cash generation improves significantly (FCF conversion went up to 146% in FY20 during Covid). This countercyclical nature of cash flows is actually desirable.

Komatsu’s dividend is quite good. The company will pay out a record 128 yen per share this year (returning the benefit of weak yen to shareholders). With this, the shares are currently at an attractive 4.3% dividend yield.

Investors can buy the listed shares in Japan (ticker: 6301) or US ADR (ticker: KMTUY)

Komatsu trades at a multiple much lower than global peers (first chart EV/EBITDA, second chart P/E)

Caterpillar trades at an EV/EBITDA of 12.7x versus Komatsu’s 7.4x - Is the difference justified? Their product portfolio are very similar. Topline growth over the last five years have been about the same. Komatsu’s management is excellent and should deserve no management discount. Caterpillar’s ROE is superior but also, Caterpillar achieves this with higher leverage. It feels like the valuation gap is more than fundamentals can justify.

At a share price of 3,000 yen, Komatsu’s market cap is 2.8tn yen (3,000 yen * 945mn shares outstanding). The company has no leverage, excluding the financing arm (which is itself conservatively capitalized and managed). This fiscal year, management is guiding 298bn yen in net income (at average exchange rate of 135.8 usdjpy) which means P/E of only 9.4x! If usdjpy stays at 150, then this will mean P/E will undercut 9x due to higher earnings.

With this kind of multiple, you don’t need a financial model. Even if you think the cost of equity capital is 10% (rates in Japan hasn’t adjusted yet), 9x P/E is equivalently saying the market thinks Komatsu earnings will shrink perpetually. The caveat with low multiple in a cyclical industry is that investors will have to be confident that they are not buying the company at peak “E”. This shouldn’t be the case because we believe mining is closer to mid-cycle today and still has ample upside.

The risk is that the world heads into a brutal economic downturn. But the good news is that over the last 20 years, Komatsu has never generated an annual loss - even during the great financial crisis and the commodities winter period of 2012-2017. And even when the yen was as strong as 79 yen to the dollar in 2011! This is a resilient company.