In this series, I explore parent-child listings in Japan as a hunting ground for stock ideas.

First, I will provide a brief introduction to parent-child listings and the evolving landscape. In subsequent posts, I will present two stock ideas that align with this theme: high quality businesses which are likely to become take-private candidates.

Introduction

Parent-child listings refers to when a parent company and its subsidiary (child) are both publicly listed.

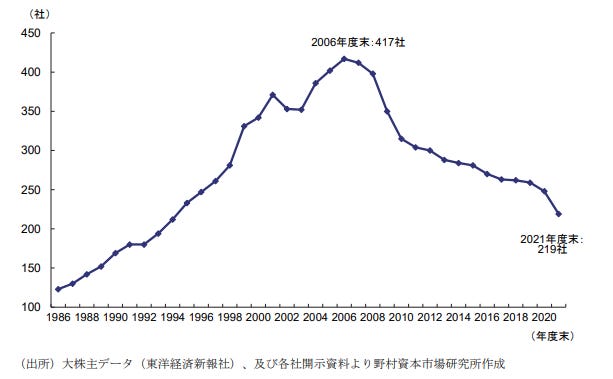

The number of parent-child listings on the Tokyo Stock Exchange reached a peak of 417 in 2006. It has been on a decline ever since then - see below graph.

Note: The parent-child relationship is sometimes defined as when the parent owns more than 50% of the child. Other definitions set this threshold at 30%. The downward trend is consistent in both cases.

A 2018 study by the Japan Exchange Group compared the prevalence of parent-child listings with other countries. In Japan, parent-child listings (using the 50% definition above) accounted for 6.1% of all listed firms, much higher than the US (0.52%), the UK (0%), France (2.2%), and Germany (2.1%).

Parent-child listings became highly popular during the 1990s. The structure allowed the parent company to raise funds while still maintaining effective control over the child. The child, by virtue of being listed, enjoys advantages such as increased prestige in the recruiting market and enhanced trust with business partners.

But over time, the structure came under increased scrutiny due to governance risks concerning the minority shareholders of the child company. The number of listings has been on a decline ever since 2007, when the Tokyo Stock Exchange began to enforce stricter exchange rules on disclosure and oversight.

In 2021, Japan's Corporate Governance Code was revised to address additional requirements for parent-child listings. This included:

Child company required to appoint independent directors (over 33% of the board, and 50% for Prime-listed companies), or establish a special committee to ensure its independence from the parent.

Parent company required to establish a governance system that protects the interests of minority shareholders of the child company.

Minority shareholders have also become more vocal. For example, large asset managers in Japan, including Nissay, Tokio Marine, Mitsui Sumitomo, Mitsubishi UFJ, Nomura, and others, have adopted voting policies that reject the re-appointment of top management in the cases where the child company fails to maintain a 1/3rd independent board.

As a result of these governance reforms, the cost of maintaining parent-child listings has become greater for parent companies. This includes both direct costs to ensure compliance, as well as indirect costs in the form of lower speed of decision making and loss of operational flexibility. This explains the on-going trend of take-private transactions, and I expect this trend to continue.

The Tokyo Stock Exchange continues to host working sessions to discuss parent-child listings, hinting at possibility of additional rules in the future (I think this is most likely for child companies listed on the Prime section, which are expected to exemplify best practices in governance).

Recent cases

The table below shows some of the high profile eliminations of parent-child listings in recent years.

I believe there are three scenarios that are conducive to elimination of parent-child listings:

When a parent company decides to significantly transform or reinvest in a child company, the presence of minority shareholders can pose challenges. Examples include Itochu's take-private transactions of FamilyMart and Itochu Techno-Solutions (CTC).

When a parent company recognizes significant strategic value in a child, and seeks to deepen business collaboration beyond mere “arms-length” interactions, minority shareholders can complicate the process. An example is NTT’s acquisition of Docomo, aimed at bringing enhanced solution offerings to the parent company.

Additionally, parent companies may engage in internal restructuring to improve their capital efficiency. For instance, Hitachi has both acquired and divested several child companies to streamline its business portfolio.

My playbook

This is easier said than done, but the goal is simple: identify child companies that are likely to be taken private. Investors can profit from a takeover premium which has averaged roughly ~30% in Japan (recently, NTT’s takeover of Docomo was at a 41% premium, Itochu’s takeover of Family Mart 47% and CTC at 20%).

Usually, the common questions are the following:

Why be happy with just a 30% return when you can look for 5-10 baggers?

What happens if a take-private doesn’t happen?

What if the take-private doesn’t happen at a “fair” price?

On the first point, I value having multiple idiosyncratic drivers of return in my investment (i.e. diversity in ways I can make money on a single idea).

Some investors “fear” being bought out at a 30% premium because it precludes further compounding from that investment. In my view it’s not the worst thing - I can simply celebrate the small win and reallocate the proceeds into other “5-10x bagger” type ideas that I have in my portfolio (rarely is the take-private idea the only cheap stock or underperformer in a portfolio with no good opportunity to redistribute the capital).

On the second point - this is why I view take-private as a “cherry on top” rather than the main thesis. The take-private part will always remain a speculation, and I need to be happy with holding the company over the long-term even if the transaction doesn’t materialize. The stock needs to be compelling on its own, even in the absence of a buyout. Even though plenty of child companies are out there, this focus on underlying business “quality” makes the process more selective.

The idea is to look for high-quality businesses that are also likely to be take-private candidates.

On the third point, such “take-unders” are a risk. Even with takeout premium factored in, there is no guarantee that valuations will be "fair". However, recent trends suggest improving conditions for minority shareholders. A Nikkei article noted that in recent years, most disputes over buyout prices in Japan have concluded with courts siding with minority shareholders.

A case in point is Itochu’s acquisition of FamilyMart. When Itochu initially offered 2300 yen per share, minority shareholders contested the offer. The Tokyo District Court intervened, mandating Itochu to increase the buyout price to 2600 yen. This adjustment raised the takeout premium from the initial 30% to 47%.

While take-unders will always be a risk, the trend of growing recognition and protection of minority shareholder rights is positive.

I hope this post has provided readers with the basics on the evolving dynamics of parent-child listings, the opportunities they present to investors, and my strategy on how to play them.

With this in mind, I plan to share two actionable stock ideas over the coming days that aligns with this theme.

If you're interested in receiving these directly in your inbox, subscribe below!

thank you for this, very informative