Japan vs Big Tech

The "digital dependency crisis" that Japan can no longer afford to ignore

Imagine a country, let’s call it “Pacifica” for now…

Pacifica imports all its energy resources—oil, gas, coal—just to keep the lights on. It runs a consistent trade deficit of physical goods, importing more than it exports, year after year.

To offset this imbalance, Pacifica relies on its natural beauty and cultural heritage, luring millions of tourists annually who flock to its temples and vibrant cities. These visitors pump money into basic industries like food and lodging, temporarily buoying the economy.

But beneath the booming tourism industry lies a glaring weakness: much of the spending in the country’s digital ecosystem—from enterprise computing to consumer devices and apps—flows to foreign firms. As a result, all of the hard-earned surplus from tourism (and more) is funneled into buying digital services from abroad.

A twin deficit in goods and services trade, coupled with a weakening currency, have resulted in Pacifica’s citizens seeing their purchasing power eroded over time. And there is no end to the structural imbalance in sight.

Maybe you’re picturing a Southeast Asian country like Thailand or Indonesia. Or a Mediterranean destination like Greece.

But you might have guessed already — Pacifica is Japan.

In this article, I want to shed some light on the significance of Japan’s “digital dependency crisis” — a crisis stemming from Japan’s failure to achieve digital sovereignty and its overreliance on US tech giants.

Put simply, US big tech has grown so dominant that it’s singlehandedly blowing a hole in the trade balance of a nation as large as Japan. Let that sink for a moment.

Can you blame Tim Cook for looking so happy here?

In 2023, Japan recorded JPY 5.5 trillion in so-called digital trade deficit. The Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI) projects this to grow to JPY 8 trillion by 2030, at which point it could surpass Japan’s annual import of crude oil.

Japan’s total goods and services trade deficit in 2023 was JPY 6 trillion, with the digital deficit accounting for JPY 5.5 trillion.

With far-reaching consequences from the FX markets to potentially transformative shifts in Japan’s digital policy, I expect it will draw increasing attention in the years to come.

A closer look

Let’s build our case from the ground up. Japan’s FY2023 current account is shown below.

A reminder:

Current account = Goods and services balance + primary income + secondary income.

Where

Goods and services balance is the net exports of goods and services.

Primary income includes income from foreign investments, such as dividends from foreign subsidiaries, interest from foreign bonds, etc. (reported net of income paid to foreign entities)

Secondary income captures one-way transfers from abroad, including remittances, foreign aid, etc. (also reported on a net basis). Secondary income is not a major component and for simplicity we will ignore it here.

In 2023, Japan recorded a goods and services deficit of roughly JPY 6 trillion (breaking down into JPY 3.5 trillion from goods deficit and JPY 2.5 trillion from services deficit).

Offsetting this trade deficit is a massive primary income surplus of JPY 35 trillion, which keeps Japan’s current account deeply positive. Some may argue that this substantial primary income surplus mitigates concerns about Japan’s trade deficits, but we’ll come back to this point later on.

But for now, let’s dive further into the goods and services components.

Goods trade deficit

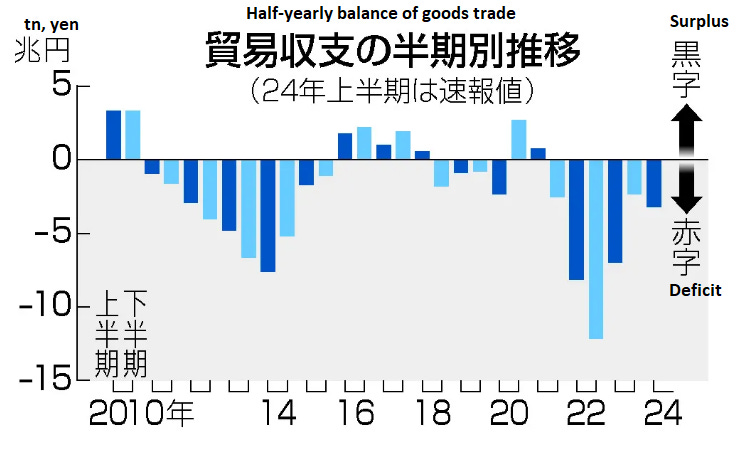

Japan has been in a structural deficit for goods trade over the past two decades. This may come as a surprise to those who have held onto the old idea that Japan is an export powerhouse.

There are several reasons for the shift:

Japanese firms have moved production overseas. This isn’t entirely negative since Japanese firms (and their profits) continue to grow, but it has contributed to a widening trade deficit.

Japan’s loss of global competitiveness in certain industries, like chips and appliances, to rivals such as South Korea.

Rising cost of imports driven by energy shocks, rising overseas inflation, and weak yen.

The third point deserves elaboration. Japan’s reliance on imported energy has long been a critical structural weakness. For example, following 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, Japan significantly reduced domestic nuclear energy production and increased its reliance on imported LNG, becoming a major contributor to trade deficit.

A similar pattern emerged post-Covid. Global oil and commodity prices surged. This was compounded by high rates of overseas inflation on general imports. On top, a historically weak yen made imports even more expensive.

Another contributor has been Japan’s reliance on cutting-edge pharmaceuticals (e.g. cancer drugs) from Western firms. This highlights gaps in R&D capabilities between Japanese and Western pharma, particularly in areas like biological drugs. Given Japan’s aging population, the demand for pharma imports will only grow.

Services trade deficit

The chart above breaks down Japan’s services trade balance.

Two components stand out:

Tourism (Dark blue bar): shifted from net deficit to a surplus in 2016 and has continued to grow, as visitor arrivals far outnumber Japanese residents traveling overseas.

Other services (Light blue bar): The majority of this category (over 90%) consists of the “digital deficit,” essentially payments made to US tech giants. The remainder includes various other services like payments to big four accounting firms.

Let’s dive deeper into this digital deficit component.

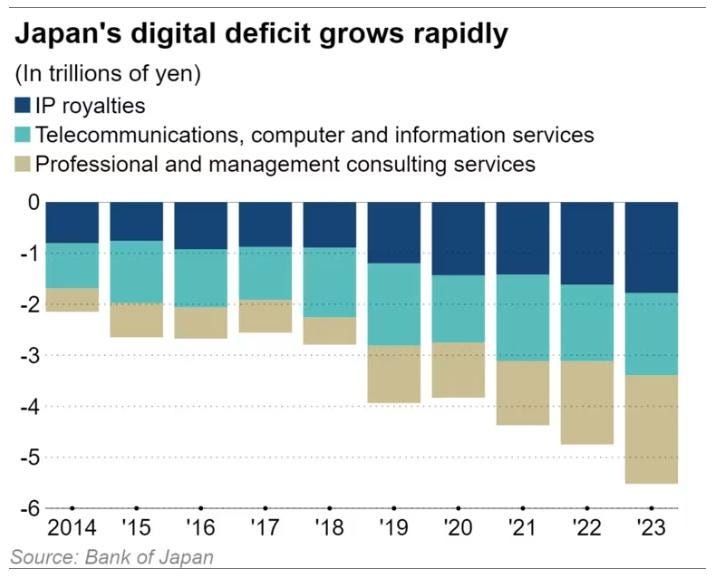

Since 2014, the Japanese government has been disclosing the digital deficit, which has grown 2.6-fold from 2014 to JPY 5.5 trillion in 2023. This is a net figure derived from JPY 9.2 trillion paid for digital services and JPY 3.7 trillion received from abroad.

The above chart breaks down the JPY 5.5 trillion deficit by its main components:

IP royalties: includes payments for OS, app stores, and apps (e.g. Apple, Android)

Telecommunications, computer, and information services: includes IT consulting and cloud services (e.g. AWS, Azure)

Professional and management consulting services: includes digital advertising (e.g. Facebook, Instagram, Google)

Not surprisingly, all three components have grown.

The picture is quite clear: on the services side, Japan is taking its hard-earned surplus from tourism and spending it all on paying for digital services.

How will this play out? While I’m personally bullish on the Japanese tourism industry, it still has natural growth constraints. However, there is no ceiling on how much Japan can continue to spend on digital services. In fact, digital services spend could accelerate given:

Japan is already playing catch-up in the digital realm, and is behind other major countries in many key digital metrics.

AI is poised to make Japan’s digital dependency crisis even worse, in a world where firms like Nvidia and those that are able to scale AI services (e.g. hyperscalers) dominate AI economics.

Without an AI champion of its own, Japan has few options if it wants to avoid being left behind in the new digital paradigm.

The myth of Japan’s current account surplus

By now, some readers might be eager to counter: “Japan has a deeply positive current account surplus!”

True, Japan owns a lot of foreign assets which generates significant income from abroad. This is recorded as “primary income,” which more than offsets the goods and services trade deficit. However, the caveat here is that much of this income doesn’t make its way back to Japan.

Let’s consider two cases:

A Japanese company owns an overseas subsidiary generating US$100 mn in profit, of which $20 mn is paid as dividend to the Japanese parent company, and the remaining $80 bn is reinvested in the subsidiary. The entire $100 mn is recorded as primary income, but only $20 mn represents the actual cash flow that’s repatriated.

Japan (through government, financial institutions, and corporations) owns a significant amount of foreign fixed income securities (mainly US government bonds). The interest earned on these is recorded as primary income, even though much of it is reinvested under an automatic reinvestment program to purchase more bonds. This income isn’t repatriated to Japan.

The two cases presented above account for roughly 60% of Japan’s primary income.

As such, rather than take the headline current account figures, it makes sense to also look at it on a “cash flow” basis. This has already been done by Daisuke Karakama, Chief Market Economist at Mizuho bank, who has created the excellent chart below. I’ve added English headings to the chart for reader convenience.

The dotted line at the top of the chart shows Japan’s headline current account surplus, which looks impressive. But when you put that into cash flow terms, it becomes the line with the pink circles (the difference between the goods and services trade balance and the portion of primary income that’s repatriated back to Japan) which has been negative in recent years.

This also explains why, at the margin, movements in goods and services trade remain very important—even if they appear small relative to Japan’s total primary income.

Implications

FX

Based on our discussion so far, does it surprise you that the Japanese yen has been weak?

“According to an analysis by Mizuho Research & Technologies, if the digital deficit doubles from the 2023 level by the end of March 2026, it will add another 5 to 6 yen of depreciation in the Japanese currency's value against the dollar.”

- Nikkei Asian Review

Or let me put it another way — would you feel bullish about the currency of a country that relies on tourism as its primary growing surplus, while ultimately funneling all those earnings (and more) into paying for essential energy imports and ever-increasing digital spend on big tech?

Of course, there are other factors which influence FX, such as interest rates, which are beyond the scope of this current discussion. However, I believe long-term FX fundamentals are inseparable from the underlying demand and supply for a currency driven by real economic activity.

Digital policy

In the coming years, we may see a significant shift in Japan’s digital policies.

Will Japan adopt the EU model of heavy regulations and fines to maximize value extraction?

Will it adopt the Chinese playbook of developing its own homegrown tech champions?

Both?

Either way, I think we are past the peak of Japan’s hand-off approach.

Donald Trump’s coming presidency adds an interesting layer to this dynamic. Trump is likely looking to renegotiate a host of economic contracts with partners and allies, including Japan. In turn, I believe Japan would be foolish to not leverage its current situation with the US big tech as its own bargaining chip.

There’s a clear parallel here. Trump has accused the Japanese automakers of hollowing out the US auto industry. But today, Japan could make a similar argument against US big tech, which has held Japan’s digital ecosystem captive and has blown a hole in the country’s trade balance.

One notable recent development is the Japanese government’s issuance of “administrative guidance” to LY Corp, urging it to reassess its capital ties with South Korea’s Naver which is one of its parent companies. LY Corp is Japan’s largest homegrown internet company — an entity formed through the merger of Line (owned by Naver), and Yahoo Japan (owned by Softbank). The current ownership structure, following the merger and subsequent restructuring, is shown below.

As you would expect, there was fierce backlash from South Korea. And given the warm ties between the two countries’ current administrations, Japan seems to have backed on its “administrative guidance” for now. However, I believe it shows the government’s hand.

(Side note: Once Japan-South Korea ties sour again, which is a matter of time given President Yoon’s downfall and the next likely candidate for South Korea’s presidency is Lee Jae-Myung who is decidedly pro-China, we will probably see this back on the table again)

Japan has also studied the EU’s heavy-handed approach closely. A recently proposed bill, if passed next year, could allow the regulator to impose fines up to 20% of annual domestic revenue on tech companies for abuse of power. If you assume a profit margin of 20%, then it means this bill can effectively claw-back all of the profits of tech firms.

In recent years we’ve seen how hard Japan has been trying to reclaim its position in the semiconductor industry. But do they only care about hardware and not its digital sovereignty? Will Japan continue to sit back and let US tech giants profit endlessly, or will it finally confront its position as a digital colony?

Finally, if there’s truth to any of this, it raises another interesting question: is now a good time to revisit the Japanese homegrown tech champions, such as LY Corp and maybe a few others?

Thanks a lot for this nice article. Do you think japanese tourism industry will continue to expand in the coming decade? Are there any good japanese tourism companies to invest in?

You cannot consider the growth rate of spending without considering the growth rate of assets invested overseas. Maybe this cash flow from abroad will grow through compounding?