IHI Corp (7013) - Part 2

Aligning with Japan's most critical needs: defense and energy security

Disclaimer: The information in this article reflects the personal views of the author and is provided for informational purposes only. It should not be construed as investment advice. The author holds a position in the security at the time of publication. Investment funds or other entities with which the author has consulting or advisory relationships may or may not hold a position in the security/securities discussed. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of any other parties. Readers should conduct their own research and consult a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

In Part 2, we’ll dive into IHI’s defense and power generation businesses. These contribute to Japan’s national security and energy needs, aligning with the country’s most critical long-term interests. We’ll wrap up with a discussion on valuation and risks, including IHI’s exposure to the recently announced Trump tariffs.

Defense business

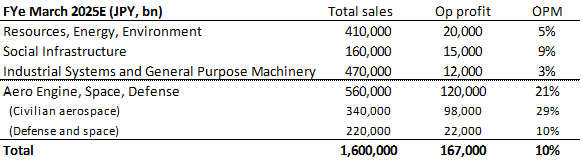

IHI’s defense segment breaks down as follows:

60-70% from military aircraft engines. IHI covers all fighter jet models used by Japan’s air force.

15-20% from rocket motors (propulsion system for missiles), and

10-15% from gas turbines for navy vessels and other defense equipment.

Japan’s air force operates Japanese variants of the U.S. F-15, F-16, and F-35. Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) manufactures these aircrafts under license from Boeing and Lockheed Martin. IHI produces the engines under license from GE and Pratt & Whitney (one exception is the F-35: IHI supplies components to P&W but does not assemble the engines in Japan ) and handles maintenance & repair for all engine models.

In addition to licensed production, IHI also develops proprietary engines. It manufactures the engines for the Kawasaki P-1 maritime patrol aircraft and the T-4 training jet using its own designs. IHI also produces the T700 engine for military helicopters under license from GE.

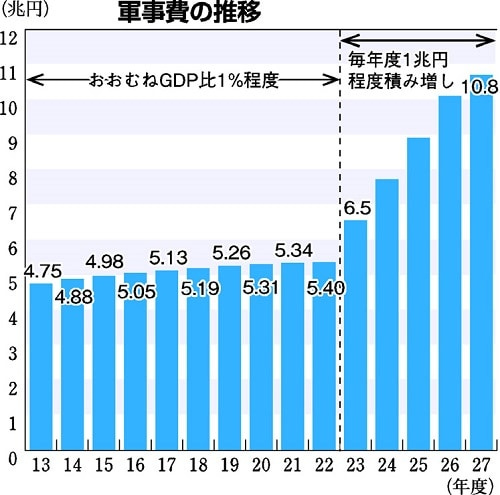

Today, Japan is on a path to increasing its defense budget to 2% of GDP by FY2027 (from ~1% historically). The chart below shows the projected increase in defense spending (blue bar, JPY trillions). To get to the 2% GDP target, Japan will increase its spending by a trillion yen every year until 2027. Cumulative spending will be JPY 43 tn between FY2023-2027 compared to JPY 27 tn between FY2019-2023.

The Pentagon has requested Japan to raise its defense spending to 3% of GDP. Although Japan has so far brushed this aside, I think this remains a potential catalyst, with some experts viewing 3% as a realistic target for Japan (now that NATO is also reportedly discussing 3% as its next goal).

The U.S. has been actively promoting so-called “friend-shoring” of the defense supply chain. Recognizing that its own industrial capacity has fallen much behind China’s, the US has been actively trying to leverage the industrial capacity of its allies.

The U.S. ambassador to Japan urged Tokyo on Tuesday to take a greater role in developing, producing and supplying weapons "to enhance our collective security" amid conflict in Ukraine, Gaza and elsewhere…The United States alone can no longer supply all democracies, Ambassador Rahm Emanuel said during a visit to a Mitsubishi Heavy Industries' F-35 fighter jet factory. He stressed the importance of stronger defense industry cooperation between the allies…The countries will now look at what Japan can co-license, co-produce and co-develop, Emanuel told reporters. "It's extremely exciting to bring Japan's industrial capability, its engineering smarts, onto the field on behalf of the alliance," he said.

- Mainichi Shimbun (link)

This “friend-shoring” push also aligns with Japan’s own incentives. Japan wants to participate in weapons manufacturing so that technological learning happens within its own border. The F-2 program (Japanese variant of the F-16 fighter) resulted in a 60% and 40% production split for Japan and US.

Raising the defense sector profit

Decades of Japan’s pacifist military policy led to many of the country’s defense contractors withdrawing from the business (it is said that in the past 20 years, over 100 defense contractors have withdrawn). As Japan looks to re-militarize, it finds itself with an inadequate domestic defense industry which has suffered from decades of underinvestment.

To rejuvenate the defense sector, Japan has committed to increasing the sector profitability. In the past, the standard profit margin on defense contracts was 8%, but contracts from FY2023 onwards will be under a new structure (below chart, right side). Effectively, the maximum operating margin will be increased to 15% from 8%, with an inflation cost adjustment component.

Missile spending explodes (no pun)

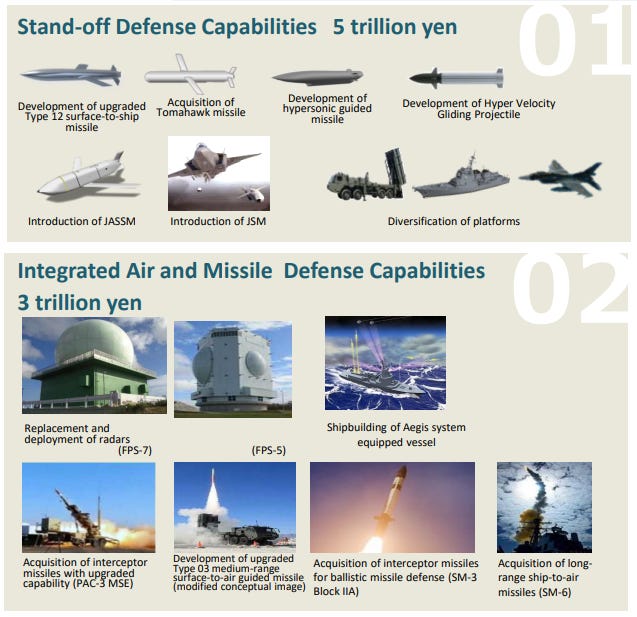

Japan’s spending on “Stand-off defense capabilities” will increase from JPY 200 bn to 5 tn (25-fold increase!) and “integrated air and missile defense capabilities” will increase from JPY 1 tn to 2 tn (Note: MoD’s published figure is 3 tn, which is larger than IHI’s 2 tn, but maybe IHI is referring to its own addressable market within the segment).

The former category has a more pre-emptive or retaliatory focus (e.g. long-range cruise missiles, anti-ship and land attack missiles) while the latter involves more defensive focus (intercepting oncoming missiles and aircrafts).

IHI’s rocket motors serve as propulsion system for missiles. Currently, IHI is supplying mainly the latter category of defensive missiles such as the SM-3 and PAC-3 (“Patriot missiles”). However, the 25-fold budget increase on the "offensive side” can become a significant opportunity if IHI can capture a portion of it in the future.

Easing export restrictions

Historically, Japan maintained very strict arms export controls. In 2014, the Abe administration replaced the existing framework to support the growth of the country’s defense exports. Since then, Japan has gradually relaxed these restrictions.

IHI has capitalized on this shift. It previously produced F-35 engine components solely for Japan, but as of April 2024, it began manufacturing engine modules for export to global F-35 operators across 18 countries. Japan has also eased export rules to allow the replenishment of U.S. Patriot missile stockpiles depleted by the war in Ukraine.

Further relaxation of export controls is expected, potentially unlocking growth opportunities in areas where Japan is seen as a technological leader, such as ships and maritime patrol aircraft. News: Italy is reported to be interested in purchasing the Kawasaki P-1 maritime patrol plane.

Finally, it’s worth noting Japan’s participation in the Global Combat Air Programme (GCAP), a joint project with UK and Italy to develop a sixth generation fighter jet by 2035 (with Saudi Arabia potentially joining). A Japanese consortium, including IHI, will hold a one-third stake in the program. What makes this significant is that Japan is stepping up as a full development partner, rather than just importing or producing US fighter jets under license.

(Side note: the most interesting thing is Japan chose European partners instead of the US — reportedly due to the US's inflexibility and unwillingness to treat Japan as an equal partner, and Japan’s desire to diversify its defense partnerships. Given what we’ve seen during Trump’s second term so far, this has proved to be a wise decision for both the Japanese and the Europeans…)

The key take-away here is that Japan is ambitious, and its main defense contractors including IHI will play a key role in supporting Japan’s climb up the defense value chain.

Resources, Energy, and Environment

This segment is expected to generate 26% of FY2025/3E sales and 12% of operating profit (before corp. eliminations).

Within this segment you’ll find several different businesses. Please note below isn’t IHI’s official disclosure — it’s my own way of categorizing them:

Manufacturing, which produces power plant and industrial plant equipment. Key products here are boilers and gas turbines. IHI also produces large diesel engines for land and marine use.

IHI Plant, which engage in EPC (engineering, procurement, and construction) across power generation, LNG receiving and storage, petrochemical, and industrial plants.

Jurong Engineering (JEL), a consolidated subsidiary headquartered in Singapore, which engage in power plant EPC in developing Asia, mainly Southeast Asia, South Asia, and the Middle East regions.

A nuclear business, which makes “picks and shovels” nuclear power plant components and structures including containment vessel, steel structure modules, piping systems, and waste facilities. IHI is also an investor in leading SMR company NuScale (IHI invested $20 mn in 2021 according to this article).

Therefore, IHI operates as an end-to-end player across both EPC and manufacturing. The EPC, which “owns” the customers, can distribute IHI’s power plant and industrial plant equipment while also providing customer insights to the manufacturing side. In turn, the EPC business benefits from having internal manufacturing capabilities, allowing greater flexibility to meet customization needs.

A significant portion of the segment’s sales comes from aftermarket. The exact figure is undisclosed, but I estimate it to be at least 50%. Key products in this segment, such as plant boilers and gas turbines, are among the most aftermarket-intensive areas, with easily over half of their sales generated from spare parts and long-term operating and maintenance contracts. Also, the nuclear business is 100% aftermarket (there has been no new nuclear power plant construction in Japan since Fukushima, so all of it comes from servicing and maintenance including decommissioning and restarts).

There are three key areas of growth within this segment:

Gas turbines

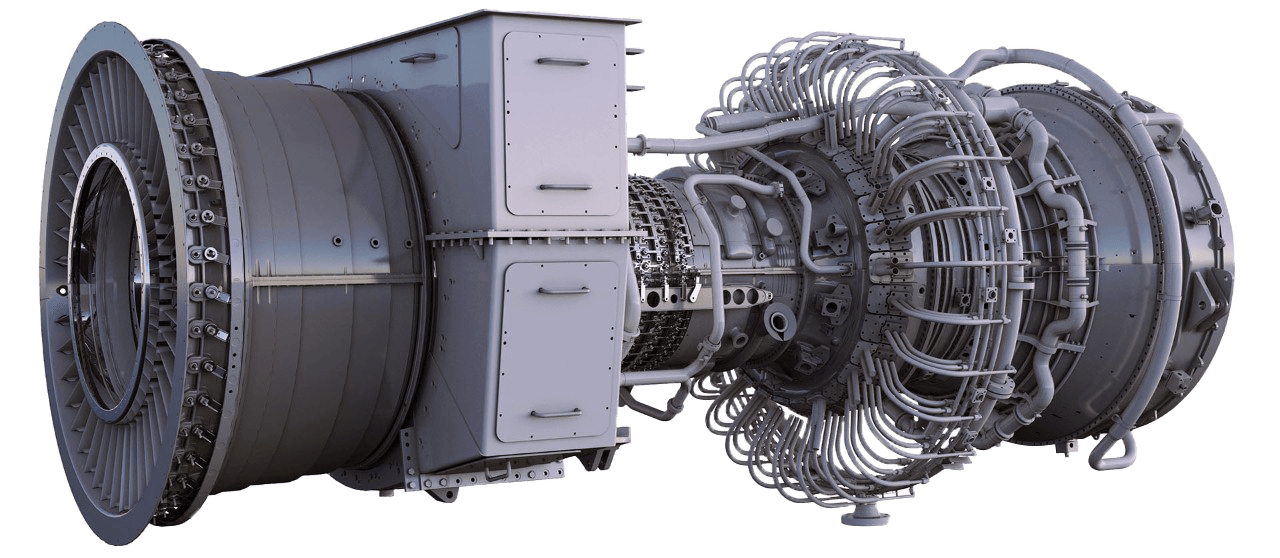

Gas turbines are the core component of natural gas power plants, and demand has recently surged to unprecedented levels.

Since the war in Ukraine, Europe has re-embraced fossil fuel and has been rapidly constructing natural gas plants. In 2025, Europe’s natural gas power generation capacity is expected to 5x YoY, leading to record orders for gas turbines.

The AI boom has been a significant driver. Data centers and new semiconductor facilities increasingly utilize their own gas turbines to generate power on-site. Mitsubishi Heavy and GE Vernova have each sold out their capacity through 2028.

According to Jeffries, 10 months ago, prices for a standard Mitsubishi J or GEV HA turbine ranged from $60-65MM, but are now up more than 50% to $85-110MM on awarded contracts today.

Three major global players in gas turbine are GE Vernova, Siemens, and Mitsubishi Heavy which controls two-thirds of the global market.

IHI’s gas turbine business consists of its own turbines and licensed production from GE. IHI’s own turbines are focused on smaller output models, mostly used in cogeneration and small industrial use cases for only the Japanese market. The more important business for IHI is its longstanding partnership (50 years) with GE to manufacture and service GE gas turbines in Asia. Currently, this includes the GE LM-series which is among the best-selling aeroderivative gas turbine models in the world. As of March 2023, IHI had 242 total gas turbines in operation (162 are the LM models), with 159 in Japan and 83 in Asia, with Thailand and Australia being the largest markets outside Japan.

The benefit of gas turbines is that it has higher efficiency and lower emissions than coal-fired boilers, and it’s been taking share away from the latter. This has led to some concern by investors that coal-fired boilers, which represents a major part of IHI’s sales, is being cannibalized. However, the reality is that the world is desperately hungry for more energy consumption. Aftersales of installed boilers will continue to be a major revenue generator for IHI, as existing coal plants will be in service for decades. During this time, many coal boilers will also be retrofitted with co-firing biomass or ammonia to reduce emissions and extend their lifetime. This is another business opportunity for IHI, as we will discuss later.

Nuclear

Over the next five years, IHI’s nuclear business will likely enter a growth phase.

A decade after shutting down all of the country’s nuclear power plants following the Fukushima accident, Japan is gradually re-embracing nuclear again to meet its rising energy demand. Japan’s new nuclear energy plan calls for “maximizing the use of nuclear energy.” Of Japan’s 33 operable nuclear reactors, 12 have resumed operations after meeting post-Fukushima safety standards. Japan aims to increase the share of nuclear in its energy mix to 20% by 2040 (up from the current 8%), and is now considering the construction of the country’s first new nuclear plant since Fukushima.

While there are lots of discussions on evolving reactor technologies, IHI’s product portfolio focuses more on the the boring “picks and shovels” part of the nuclear power plant. This makes IHI less vulnerable to rapid technological changes.

For example, a major area for IHI is containment vessels, which is an extra thick, high-integrity structure that surrounds the main reactor pressure vessel (where the fission occurs). The containment vessel serves as a safety barrier, forming a second line of defense in the case of reactor failure. Even as nuclear technology advances, the fundamental need for a physical containment structure to prevent accidents remains the same. Can you imagine regulators saying “we no longer need safety barrier for our new generation of reactors”?

IHI’s investment in leading SMR player NuScale is providing IHI an opportunity to learn advanced SMR designs. Through this, IHI is repurposing its nuclear portfolio for future SMR deployments (both in Japan and overseas), including the development of new containment vessel designs for SMRs. Management has announced plans to deploy its first SMR project in the United States in 2029.

Ammonia

“The Group targets approximately 900.0 billion yen in 2050 as revenue from the entire Ammonia Value Chain business…In terms of profitability we currently anticipate a profit margin equal to the average of the IHI group”

- IHI

JPY 900 bn from the ammonia business alone is quite a significant figure, considering the total revenue of the resources and energy segment today is around JPY 420bn.

Ammonia 101

Ammonia (NH3) is one of the most common industrial chemicals, used mainly in the production of fertilizers and other industrial applications.

Ammonia burns cleanly, and is being explored for its role in power generation. However, its properties makes the combustion process technically challenging to manage. IHI is spearheading the development of technology which allows conventional power generating equipment, such as gas turbines, to be able to effectively burn ammonia as fuel (IHI leveraged its knowhow from its jet engine combustion technology, taking 10 years to develop a proprietary method for ammonia combustion).

The idea is to start by mixing a certain percentage of ammonia with fossil fuel, so that we end up using less volume of fossil fuel to achieve the same energy output. This is called ammonia “co-firing”. First, it will be done at a ratio of 80% fossil fuel (coal or natural gas) and 20% ammonia. Over time, the ratio of ammonia will be increased as technology improves. Ultimately, the goal will be to burn 100% ammonia.

Thus, ammonia can be thought of as a “transitional” fuel source, although it also has a potential to serve as an “end-state” fuel source once we get to burning 100% ammonia. It’s similar to the concept of hybrid cars being a transitional solution to a full EV, if you like this analogy.

Is Japan crazy for going down the ammonia path?

Japan has announced plans to utilize ammonia for 1% of total power generation by 2030 (through co-firing), and 10% of the country’s total power generation by 2050.

Japan’s enthusiasm for ammonia is unique among G7 nations. Most other members have taken on an “all or nothing” approach, viewing transitional fuels like ammonia as largely a waste of time and advocating for the direct transition to renewables such as wind and solar.

What we are starting to see, however, is that climate goals have proven to be unrealistic. Europe has been quietly turning back to fossil fuel. It reminds me of what’s also happening in the auto market. Toyota’s hybrid sales are currently reaching record highs, years after the company was mocked for being slow to embrace a pure EV future. Perhaps Japan’s focus on transitional solutions, whether hybrid vehicles or ammonia, is more practical and grounded in reality than many have given it credit for.

After the Fukushima nuclear accident, Japan shut down all of the country’s nuclear power plants and built many new coal and gas fired plants (see below chart). Ammonia provides an effective way to “off-ramp” these fossil fuel plants in the coming decades, while still keeping them in operation for as long as possible. This is the key reason why Japan is highly focused on ammonia.

The usefulness of ammonia extends beyond Japan, however. Many developing markets are in a similar situation, having built a large number of coal power plants recently to meet the growing energy needs of their population. Renewables like solar and wind remains out of reach for them, and they need a practical solution to transition their coal plants while keeping them in operation for as long as possible.

IHI therefore sees developing Asian markets as a high potential market for its ammonia technology. Countries like India, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand are giving ammonia a serious look. Another key point is that these countries, like India and Indonesia, are gearing up to produce green ammonia for export to Japan. If they are going to become major producers, it only makes sense that they seriously consider its use for their domestic market as well.

It helps tremendously that IHI has a large presence in developing Asia through its subsidiary Jurong Engineering, a scaled player in the Asian power EPC market. Jurong’s established relationships with power plant operators in the region helps it to influence customer roadmaps and promote the ammonia technology. With Jurong owning the customer relationships and IHI the ammonia technology, this is a good example illustrating the advantages of IHI’s end-to-end capabilities.

Main challenges: supply and cost

Ammonia is nothing new; it’s already widely used in the production of fertilizers and many industrial applications. Hence, there’s already existing infrastructure for shipping and storing ammonia. A huge advantage of ammonia is that it’s relatively easy to store and transport. Unlike hydrogen which needs to be cooled to -253 degrees to liquify (versus only -33 degrees for ammonia), ammonia does not require highly costly and specialized supply chain.

“Ammonia is easy to handle. We have the infrastructure to handle ammonia now. We just modify it, scale it up and make it safe. That is the quickest way to get to carbon neutral. It is the best way to do that compared to hydrogen and other sources”

– Akihiko Numazawa, IHI (source: Financial Review)

GE (biased they may be as they are IHI’s partner) has also stated:

Hydrogen has been hailed as the decarbonization “Swiss Army knife,” but ammonia could actually be closer to cracking the code and becoming the end-to-end solution the world really needs. Hydrogen remains an important focus for GE Vernova, but unlike ammonia, it can’t affordably or easily be shipped across oceans.

- GE Vernova

IHI estimates global ammonia demand will reach 700 mn metric tons by 2050 which includes all use cases. Japan will require 30 mn tons for power generation by then. Today, the global ammonia supply is roughly 200mn tons, and out of this, about 20 mn is available in the export market (the majority of ammonia is being consumed in the market it is produced). Even assuming Japan can secure all the freely traded ammonia in the world right now, it will still not be enough to satisfy Japan’s future demand.

The main challenge with ammonia is hence the supply. Japan will need to secure additional ammonia at an acceptable cost. What makes this particularly challenging is that the ammonia must also be clean (“green ammonia”).

You see, while ammonia burns cleanly, the production process to manufacture ammonia may not be clean (just like EV batteries). Ammonia production always requires hydrogen, but the environmental impact depends on how that hydrogen is produced. Obviously, clean ammonia costs way more than dirty ammonia.

“Gray ammonia”: dirtiest form produced using fossil fuels, involving applying pressure and high temperature to natural gas (methane), which emits CO2 in the process.

“Blue ammonia”: produced using fossil fuels, but with 80-90% of CO2 emissions captured by CCS (carbon capture and storage) technology to store it underground.

“Green ammonia”: produced using renewable energy to split water atom (H2O) using electrolysis.

Currently, all ammonia in the market are gray, as blue/green ammonia are not yet mass produced. From 2027, Japan plans to start the import of blue ammonia, and starting in 2028-2029, green ammonia capacity will start to come out as well. Cost is the big issue, however. In the initial stages, to support the adoption, government subsidies will likely play a big role.

I believe the ability to procure blue or green ammonia at a low enough cost will be the key element that makes or breaks the ammonia roadmap. This is a key risk for the ammonia strategy that needs to be monitored.

Significance for IHI

We are still in the very early stages with lots of unknowns for the ammonia roadmap. However, if we get there, IHI will be in a position to lead the industry.

IHI and Mitsubishi Heavy are the only two companies investing in ammonia power generation. The Japanese market will be a duopoly, with IHI and MHI likely leading the Asian markets as well.

IHI has reached two critical milestones.

In 2022, IHI successfully demonstrated a 100% ammonia burning gas turbine, the first in the world. While it was achieved in a small-scale 2 MW gas turbine, this was an important technological proof of concept to show that ammonia can serve as a single fuel source.

In 2024, IHI successfully completed the world’s first large-scale ammonia “co-firing” (20% ammonia) demonstration. This is significant, because it was conducted at 1GW output (the scale of a major city’s power supply), demonstrating ammonia co-firing is viable at commercial scale.

IHI has another key advantage: partnership with GE. IHI and GE are co-developing gas turbines capable of burning 100% ammonia, aiming for commercialization in 2030. They are looking to equip GE’s existing 6F.03, 7F and 9F models with IHI’s proprietary ammonia combustion technology. For IHI, this is major win for another reason. GE’s 6F.03, 7F, and 9F are heavy-duty models designed for large-scale utility use, which IHI currently lacks in its lineup. Until now, IHI’s gas turbines, including the GE-licensed LM series (LM2500, LM6000), have been aeroderivative models which are not suitable for large scale deployments. With this collaboration, IHI moves up the value chain and expands its lineup (see the chart below).

In 2023, a MoU was signed with Singapore’s Semborp, which operates two GE 9F gas turbines at its Singapore-based power plant which will be retrofitted with ammonia-firing capabilities by IHI. According to GE Vernova: “If this large-scale experiment proves successful, it could pave the way for worldwide adoption of a lower-cost, lower-carbon alternative fuel for gas turbines.”

IHI is not just offering a “point solution”. It will be involved across the entire ammonia value chain, including power generation (gas turbine and boilers), ammonia shipping and receiving terminals, and ammonia production including providing equipment for green ammonia synthesis and investment participation in producers.

With these in mind, what I think could happen is that IHI will become thematically tied to ammonia at some point. If the world starts reconsidering the role of transitional energy solutions like ammonia and more countries gradually start to incorporate ammonia into their energy mix forecasts, especially in developing Asia, I think IHI has significant room to re-rate further as the regional (and possibly global) leader.

In fact, this has happened with Japan Engine Corp (6016), which is a marine engine maker that’s part of the Mitsubishi keiretsu (MHI owns 14.8%).

In May 2023, the company announced it has successfully tested ammonia co-powered engine for large ships, and in January 2024, it announced the planned delivery of the ship in late 2026. These sent the shares soaring (see above chart).

But perhaps what the market missed was that in the same press release, it was announced that IHI is also part of the consortium that’s building this ship! MHI is the largest shareholder of Japan Engine Corp, so it’s intriguing that IHI (a competitor) even has a seat in the consortium. I see this as a strong endorsement of IHI’s ammonia technology. It’s increasingly looking like IHI and MHI will be duopolizing every business related to ammonia power generation in Japan, from land to sea.

Valuation

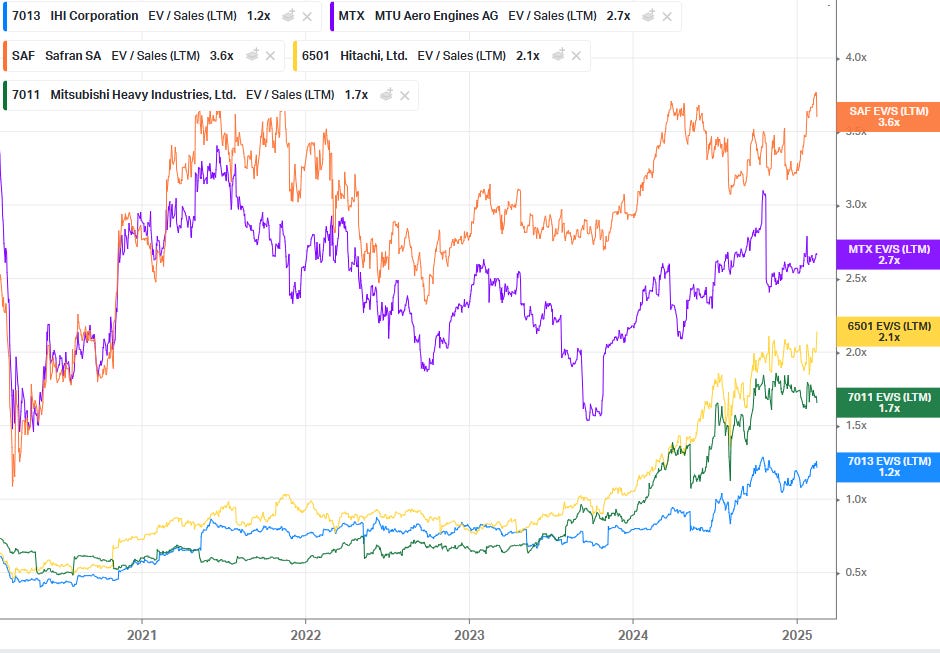

As shown below, IHI is much cheaper than both its Japanese peers (MHI and Hitachi) and overseas peers (MTU and Safran).

The figures in the above chart doesn’t adjust for IHI’s investments and real estate holdings. Adjusting for these, I’ve calculated IHI’s EV/EBIT to be 9.2x and EV/sales to be 0.83x.

Market cap: JPY 1.36 tn (share price: JPY 9000)

Net debt and minority interest: JPY 311 bn and JPY 26 bn

Equity method and other financial assets (includes policy shareholdings): JPY 113 bn.

Real estate portfolio at fair value: JPY 341 bn. Apply a 30% capital gains tax on the difference between fair value and book value (JPY 34 bn), leaving JPY 249 bn net of tax.

FY2025/3 sales and EBIT forecasts of JPY 1600 bn and JPY 145 bn

If we apply MTU and Safran’s EV/EBIT multiple on IHI’s aerospace segment EBIT, we get JPY 2.5 to 3 tn. Even if you argue IHI’s business is not as high quality and deserve a 30% discount to these peers, that’s still JPY 1.8 to 2.1 tn in just the value of the aerospace segment. Today, we can buy all of IHI for JPY 1.3 tn.

We haven’t even considered the resources & energy segment and rest of the company, which collectively generates JPY 1 tn in revenue and JPY 47 bn in EBIT, and has exposure to valuable growth areas like gas turbines, nuclear, and ammonia. How much are these worth? If we value these at 10-20x EBIT, the rest of the company are worth another JPY 0.5 to 1 tn.

Plus, IHI owns 35% of Japan Marine United (#2 largest shipbuilder in Japan). Under equity method, this is recorded on IHI’s balance sheet at only JPY 9 bn, valuing the entire company at 25bn. Note that in FY2024/3, JMU generated JPY 286 bn in revenue and 4 bn in profit.

I believe IHI’s shares can 2-3x before it reaches its fair value. I also think IHI can fairly easily overshoot this too, thanks to geopolitical optionality and the scarcity of high-quality defense names in Japan.

Risks

Tariff risk: IHI’s exposure to Trump’s latest round of tariffs is as follows:

North America sales (no separate disclosure for USA):

Note:

Tariff exposure of the “Industrial Systems and General Purpose Machinery” segment could be much lower, since IHI owns a production facility in the US (IHI Turbo America) for producing vehicle turbochargers, its main product.

All civilian aerospace parts are produced in Japan and will be fully subject to tariffs.

Operating profit:

Therefore, roughly 20% of IHI’s total sales (90% of civilian aerospace sales) and 50-60% of operating profit are at risk due to tariffs.

Flows-related risk: Ceasefire in Russia/Ukraine could lead to sector rotation out of defense names. Slowdown in air travel (passenger traffic decline) could also result in rotation out of aerospace.

GTF engine: GTF program is recovering from its costly recall incident, and things would have to go smoothly from here. Any further recalls or incidents could cause irrevocable reputational damage. At this point, we have to trust that P&W has things under control, and that the nature of the recall incident was indeed a “one-time manufacturing defect,” as opposed to, say, something fundamentally unsound with the core technology of the engine itself, which could undermine the entire GTF program.

Ammonia becomes a money sink: If ammonia turns out to be an unrealistic solution for power generation, then that will impair all of the work and development IHI has put into this area.

Dependency on GE partnership: IHI lacks proprietary technology in areas like gas turbines and has heavy reliance on its partner GE. I believe GE has been highly focused on capital efficiency (especially since Larry Culp took over as CEO in 2018), and will be keen to continue to rely on co-development partners like IHI for its non-core markets. The upcoming energy transition should increase GE’s reliance on regional partners more (e.g. GE isn’t looing to invest in ammonia, given limited market opportunity in North America).

IHI obviously comes with its share of risks, but the good news is that the thesis spans multiple angles — from governance reforms to civilian aerospace, defense, and power generation. In other words, there are multiple ways to win, and enough diversification to size this up as a large position without losing much sleep.

Thanks for reading!

![April Fools 2024] Mitsubishi F-2 Super Kai - An Unreal Overpowered Zero - Passed - War Thunder — official forum April Fools 2024] Mitsubishi F-2 Super Kai - An Unreal Overpowered Zero - Passed - War Thunder — official forum](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!zno9!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa3c93215-ac73-4f83-a8de-d4a7bb4431fb_966x720.jpeg)