IHI Corp (7013) - Part 1

Japan's leading aerospace conglomerate follows the "Hitachi playbook" to unlock value

Disclaimer: The information in this article reflects the personal views of the author and is provided for informational purposes only. It should not be construed as investment advice. The author holds a position in the security at the time of publication. Investment funds or other entities with which the author has consulting or advisory relationships may or may not hold a position in the security/securities discussed. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of any other parties. Readers should conduct their own research and consult a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

IHI has had a great run in the last 12 months (along with the other two Japanese heavy industry names, MHI and KHI). Although the stock is no longer trading at 3,000 yen like it did a year ago, I still think it’s compelling at 9-10k yen.

For some context, here’s my journey with IHI. A year ago, I built a 5-6% position at an average price in the low 3,000s. In 2024, the stock tripled. When it hit around 8,000s in Q4 I gave into the temptation to “risk manage” and trimmed half of my position. After some reflection, I began to think I took money off the table too soon. So in January, I bought back the position and some more (again, in the low 8000s). As of today (April 2) IHI is a 19% position for me.

This deep dive (>11k words) will be split into two parts:

Part 1: IHI’s value-unlock strategy, looking at how IHI is adopting the “Hitachi playbook” (which resulted in Hitachi’s stock becoming a seven-bagger in five years). We will also dive deep into IHI’s civilian aerospace engine business.

Part 2: IHI’s defense business and the company’s resources and energy segment, and valuation/risks.

Below is a summary:

Thesis summary

IHI is one of Japan’s oldest industrial conglomerates, tracing its origins back to the Ishikawajima Shipyard in 1853. Today, it operates a diversified business portfolio spanning aerospace and defense, resources and energy, social infrastructure, and industrial systems and machinery. IHI enjoys high market shares and significant barriers to entry across multiple business areas.

Shareholder value unlock

For most of its history, IHI was a sleepy Japanese conglomerate with total disregard for shareholder value. However, this is changing as I believe IHI’s management is serious about transforming. Hitachi is a compelling case study. It shows us how much these century-old conglomerates can evolve, and I think IHI is now following in Hitachi’s footsteps: prioritizing capital efficiency through selection and concentration of business portfolio, divesting non-business assets including real estate and policy shareholdings, improving WC and cash flows, and expanding its recurring revenue (lifecycle business) and profit margins.

The value unlock story is still quite recent. It’s only been a few quarters since it has really started, and it usually takes time for investors to gain confidence in these things (AND especially IHI which was terrible historically). This is why the opportunity still exists, in my view. Hitachi is now a consensus “shareholder friendly” name but it took years for this perception to crystallize.

IHI is “moated” and enjoys strong business growth

In the civilian jet engine business, IHI is the leading partner in Asia to GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney (RTX), the #1 and #2 global jet engine OEMs. In my view, IHI is the most important and highest quality aerospace name listed in Asia — something investors should increasingly recognize over time. The business is enjoying growth amid a tight aerospace market in both new deliveries and aftermarket. It’s worth noting that historically, air traffic has only declined five times in the last five decades. A key driver is MRO (an area that IHI has historically under-earned) and management expects its MRO sales to quadruple in the coming years.

IHI is also a major defense contractor, involved in the production and aftermarket for every model of fighter jet engine used by the Japanese air force. It’s involved in Japan’s 6th generation fighter jet development (a global partnership with UK and Italy) and also has exposure to missiles, one of the most significant areas of Japan’s defense spending increases.

In the resources and energy segment, IHI is an end-to-end player in Asia’s power generation value chain, operating across both EPC and manufacturing. It manufactures and services gas turbines (where it’s a partner to GE Vernova in Asia) and one of the two key players (along with MHI) in Japan’s emerging ammonia value chain. IHI also has a nuclear business where it produces containment vessels and other key components for nuclear power plants. Another little-known fact: IHI is an investor in NuScale, the leading player in SMR (small modular reactors). It also owns a 35% stake in Japan Marine United, Japan’s second-largest shipbuilder.

Valuation, catalysts, and flows

Valuation: At 9,000 yen per share (EV/EBIT at 9.2x), IHI trades at less than half the multiple of its domestic peers (MHI, KHI, Hitachi) and international peers (MTU, Safran).

Given the similarity of their businesses, I think IHI’s aerospace segment deserves a “MTU/Safran-like” multiple. If investors are willing to value IHI on this basis, then the value of IHI’s aerospace segment alone would exceed IHI’s entire market cap today. This means all the other businesses, which generates more than JPY 1 trillion in revenue combined, are unaccounted for.

Catalysts: it may appear that the “defense” theme has played out already, but I think we are still in the early stages in terms of the positive news-flows to come, including potential upward revision to Japan’s defense spending (3% of GDP) and further easing of arms export restrictions (e.g. Italy’s reported interest in purchasing Japan’s P-1 plane, which by the way uses IHI’s engine). Even after the notable run-up we’ve seen, I find myself asking “what if we are not bullish enough on defense” (yes, crazy I know).

Flows: the market sees IHI as a defense name (even though defense is only 10% of its revenue), which means stock performance is heavily tied to the flow of hot money playing the defense theme. However, within this I see two opportunities for IHI:

Fund managers have crowded into Hitachi and MHI as consensus longs. Going forward, IHI could serve as a reservoir for owners of Hitachi and MHI as they look for a similar but cheaper alternative (note that IHI is currently 1/13th the market cap of Hitachi and 1/5th the market cap of MHI).

European managers are revisiting their ESG policies to potentially remove investment restrictions on the defense sector. There are reports that Amundi, Europe’s largest asset manager, has been working on the launch of European defense ETF, along with Vaneck following suit. Fund flows into defense names may still be in the early stages.

Despite the recent run-up in stock price, I continue to see IHI as a compelling bargain, with a potential upside of 2-3x to reach its fair value, and also a good chance to overshoot its fair value given the geopolitical optionality. My price target (if that means anything) is 30k yen.

Once again, this is only the personal opinion of the author and NOT investment advice.

Value unlock

Following in Hitachi’s footsteps

By the time I heard about Hitachi’s incredible turnaround, I had completely missed it. Actually, I met Hitachi’s CFO back in 2013, shortly after starting my buyside career. Looking back, they had already started their transformation. I was too skeptical in thinking anything could change, and my status quo bias (i.e. lazy mind) was ultimately proven wrong.

So when I started noticing signs that IHI was following a similar path, I paid attention. Then, progressively over the course of the past year, the signs became more and more clear. My conviction grew that IHI could be the next Hitachi.

So let’s look at what Hitachi did.

Between 2006 and 2010, Hitachi lost USD 12.5 bn. In 2008 alone, it posted a record USD 8.1 bn loss, which was the largest single-year corporate loss in Japanese history at the time. Hiroaki Nakanishi, who became CEO in 2010, is credited with initiating the transformation efforts, which were carried forward by his successor, Toshiaki Higashihara, after he took over in 2016. Interestingly, Mr. Nakanishi was a “lifer” at Hitachi — an insider who had spent his entire career at the company (Mr. Higashihara too).

This contrasts with the typical American approach, where an outsider CEO with strong credentials is brought in to shake things up. Hitachi instead executed its transformation entirely from within (another example of a transformation from within is Nippon Steel, which I have covered in this article). The point is that in Japan, corporate transformations often start without much fanfare. As a result, it’s easy for investors to miss unless you’re paying very close attention.

However, a clear sign that Hitachi was serious about change was when it executed on its selection & concentration strategy, selling one business after another. This included: sale of HDD business, TV production, merging with rivals for thermal power generation and HVAC, sale of Hitachi Kokusai’s semiconductor equipment business and Hitachi Koki (power tools) to KKR, selling the medical imaging business to Fujifilm, sale of Hitachi Chemical, the car navigation business, and sale of Hitachi Maxell. Altogether, the number of consolidated subsidiaries decreased from 963 in 2012 to 696 in 2023.

Another transformation which was happening at the same time was moving from a hardware-based to a solution-based business model. Hitachi emphasized subscription services & long-term contracts (leading to more recurring revenue rather than one-off sales), as well as prioritizing working capital efficiency and profitability.

The result? See below stock chart. The path wasn’t linear. While turnaround efforts began in the early 2010’s, it took a while with several bumps along the way until the very dramatic re-rating in the early 2020’s.

What about IHI?

IHI’s transformation is also a “change from within” story. Mr. Ide, who became CEO in 2021, has been with the company since 1983.

Like Hitachi, IHI also appears to have been galvanized into action by a major crisis. In IHI’s case, it was FY2023 which was the second largest loss in the company’s history, caused by a massive recall in its civilian engine business related to issues with the new P&W1100G engine (a problem which wasn’t even directly IHI’s fault — we’ll come back to this story later).

After posting disastrous earnings, IHI started to talk about transforming its business portfolio, including divesting underperforming businesses, a topic which management has never been explicit about in the past. From that point, the messaging only grew louder, to the point where by Q2 FY2024 this topic had dominated IHI’s corporate presentation.

A clear theme has emerged: selection and concentration. The slide below shows how serious IHI is. What they are saying here, basically, is that they are placing every business outside of aerospace/defense and ammonia (key growth drivers) under strategic review — that’s 60% of their revenue that could be on the chopping block.

To take things a step further, IHI has begun to track its divestitures (in my view, a clear signal that it is committed). So far the company has announced the sale of its material handling system business and the general-purpose boiler business. On March 7th, the company announced the sale of IHI Construction Machinery (1% of total sales and 7% of social infrastructure segment sales). Management has been making clear progress here.

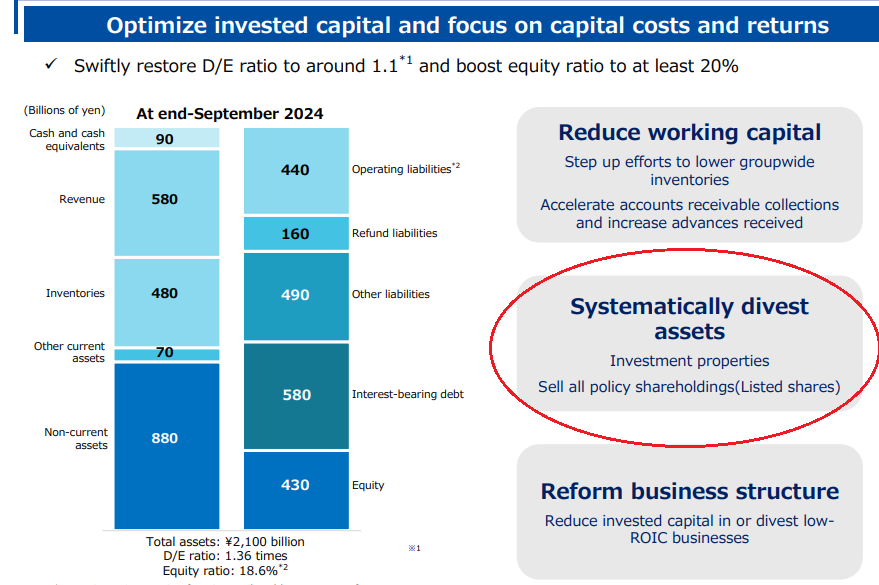

In addition, IHI has also announced plans to sell non-operating assets, including:

Policy shareholdings: IHI has committed to selling all of its policy shareholdings (see below slide). Notice the language here. Most Japanese companies tend to use softer language (e.g. “reviewing” their investment portfolio), whereas IHI commits to selling all.

Real estate holdings in Toyosu: IHI owns prime real estate in Toyosu, a redeveloped waterfront district in Tokyo that was once home to the company’s shipbuilding operations. Over time, Toyosu has transformed from an industrial area into a major commercial and retail hub, with high-rise offices and shopping centers. IHI currently leases land and office buildings occupying a total of 5 hectares (12.4 acres). The fair value of its investment real estate assets was disclosed to be JPY 341 bn, with a book value of JPY 134 bn (as of March 2024).

Finally, IHI is actively transforming its business model, shifting to a solution-based model emphasizing aftermarket sales. They use the term “LCB” (lifecycle business) to refer to aftermarket sales. The contribution of aftermarket as a proportion of the firm’s total revenue has been steadily growing, as shown below.

IHI has an ROIC target of 8%. The company is on track to achieving ROIC of 10.5% in FY2025/3 (they may have to come up with a new target soon). Management performance bonuses are directly tied to achieving ROIC target, alongside net profit and operating cash flow as KPIs.

Currently, 4 out of 12 directors of IHI are independent (still a long way from Hitachi which is 9 out of 12 independent directors, including an independent Chairman of the Board). IHI recently announced the appoint of Mr. Kenichiro Yoshida (no, not the Sony CEO, but same name) as independent director, who is ex-Ichigo Asset Management and currently an advisor for engagement investing at Aozora Bank. Adding an equity market professional as an independent director is yet another sign that IHI’s management is committed to shareholder value.

Business portfolio

For the remainder of the report, I will focus on two key segments: aero/defense and resources/energy. These segments serve as IHI’s primary growth drivers and together generates 84% of the company’s profit.

Aero engine, space & defense segment

This segment is expected to generate 72% of IHI’s FY2024E operating profit (before corp. eliminations). Between FY2024E to FY2030, segment sales is forecasted to grow from JPY 540 bn to 800 bn. The defense business is forecasted to grow from JPY 155 bn to 250 bn, which implies civilian jet engine and space will grow from JPY 385 bn to 550 bn.

Here, we will focus on the civilian jet engine business, then in Part 2, we will discuss the defense business (we’ll skip the space business as it’s not financially material).

Industry overview

Japan has three major aerospace companies: IHI, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) and Kawasaki Heavy Industries (KHI). In the civilian market, all three are consortium partners to global engine OEMs, with IHI the largest of the three. In defense, MHI and KHI rank as Japan’s top two defense contractors, as they manufacture complete military aircrafts, whereas IHI is an engine pureplay. As a result, MHI and KHI generate higher total aerospace revenue than IHI, although IHI is the most dominant within engines with 70% market share of Japan’s total jet engine production across both civilian and military.

Globally, IHI’s closest peer is MTU (Germany), which can be seen as its larger counterpart. They are quite similar, but the key difference is that MTU operates a highly successful, industry-leading independent servicing/MRO business and for this reason MTU is considered a higher quality company.

Then there are the engine OEMS, which traditionally includes three players: GE, Pratt & Whitney, and Rolls Royce. Safran (France) occupies a unique position. Some would say Safran is an OEM given its 50/50 joint venture with GE in CFM, while others argue that it’s not technologically on par with the major OEMs, and that it straddles somewhere in the middle between a partner (e.g. IHI, MTU) and an OEM.

The chart below illustrates value chain.

Business model

Investors must understand two key features of the civilian engine business: 1) Consortium structure and 2) Aftermarket.

Companies like IHI and MTU are partners in an engine development consortium, rather than a traditional supplier. The consortium can take on two forms: JV or RRSP (risk and revenue sharing partner). We won’t get into the technical differences between the two, but both function similarly in that all partners share the economic upside and downside of a project over its lifespan based on pre-agreed upon percentage allocations.

The industry has adopted a consortium model rather than a simpler OEM-supplier relationship due to the unique characteristics of the business:

Engine development is very costly and risks are high. The model helps to mutualize the financial burden and risk among participants.

A high degree of collaboration is demanded, both from technological and regulatory perspective, going beyond what is typical in a standard OEM-supplier relationship.

Jet engines are mission critical components with long lifespan. The structure ensures long-term alignment, incentivizing partners to prioritize long-term reliability and performance.

The below slide shows IHI’s engine portfolio and the economic split for each program. Usually, the engine OEM retains the majority stake (50-66%). Historically, IHI has received on average allocation in the mid-teens. OEMs takes the largest share because they handle the most technologically complex parts of the engine, along with leading the design, testing, regulatory approval, and marketing efforts.

Aftermarket is another key feature of the business model. In a given year, 60-70% of IHI’s revenue in this business comes from aftermarket.

At the program level (which spans 40-50 years), the first decade of commercial production is loss-making. Two reasons: 1) The development cost must be amortized, and 2) Engines are often sold at a loss to secure market share and lock in the long stream of aftersales revenue.

At the individual engine level (20-25 years lifespan), engines begin requiring more frequent maintenance (overhauls) after year five, driving significant aftermarket revenue. Over an engine’s full lifecycle, 80% of total revenue comes from aftermarket, with only 20% from the initial sale of the engine.

Moat

Does IHI have a moat in this business? Absolutely. This is actually easy to see. IHI has secured a role in the successor programs of every engine consortium it has participated in. Namely,

V2500 —> PW1100G

GE90 —> GEnx and GE9X, and

CF34 —> GE Passport

Not only that, but IHI’s program share has increased from first generation to second generation. Its allocation increased from 14% in the V2500 to 15% in the PW1100G, and from 9% in the GE90 to 13% in the GEnx and 10% in the GE9X. This is clear evidence that OEMs are increasingly reliant on IHI, suggesting that IHI’s moat is widening.

“I would say the engines have become far more complex…these engines are way more complex and the technology has matured. Those partners have been key, and they have a lot of IP as you stated earlier. They have a lot of IP themselves now that the OEMs are not privy to or can't use.”

- Former Associate Director at Pratt & Whitney (Alphasense, May 25, 2023)

There are three elements to understanding the moat (and why it’s widening).

Design and certification-related: As the above quote highlights, consortium partners like IHI hold key IPs. OEMs don’t design engines from scratch. Each new generation of engines builds off on the technological foundation of its predecessor, creating a lock-in effect. OEMs must rely on partners’ IP. Not doing so would be extremely costly from a design and regulatory certification standpoint, making it almost impossible for OEMs to push out or exclude their consortium partners.

Jet engines are at the front and center of aerospace innovation: Engines are the most innovative part of an aircraft. It’s where most of the performance and efficiency gains of an airliner comes from (see below quote). The technology doesn’t sit still, and that’s important because it means it’s hard for IHI’s business to get commoditized. OEMs constantly rely on their consortium partners to step up their capabilities, so OEMs can realize their own design ambitions. For instance, IHI produces modules that achieve optimal integration, resulting in weight reduction and better efficiency.

“I would say, on average you can get about 0.75%-1% year-over-year of engine performance improvement. Over 20 years when you launch a brand new program, you would expect roughly 20% every 20 years out of a new engine program.”

- Former Chief Commercial Officer at Airbus (November 16, 2023, Alphasense)

IHI has grown its program share, contributing to the industry’s increasing need for specialization. In the early days of jet engines, OEMs made everything in house. Over time, partners like IHI took on more of the manufacturing, delivering specialized modules which allowed OEMs to concentrate on pushing the envelope on the most critical and high-value parts within the engine (e.g. the geared-fan system in the PW1100G). As engines grow more complex, the industry is moving further towards specialization, and consortium partners are enablers of this. This reflects both consortium partners’ growing technical capabilities as well as the OEM’s desire for greater specialization (to remain competitive in their field).

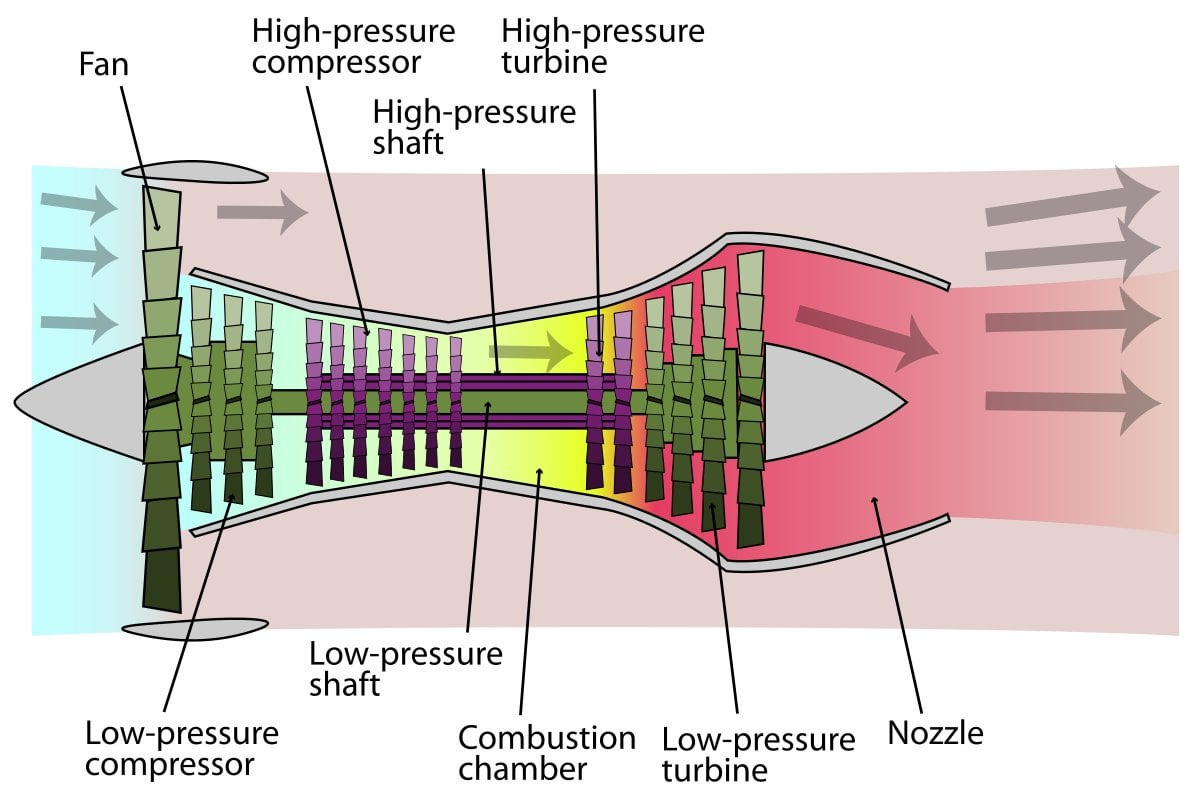

Typically OEMs concentrate on the “hot section” of the engine, which operates under extreme stress. This includes the high pressure turbine, high-pressure compressor, and key components in the combustion chamber. Consortium partners modularize other areas such as the low pressure turbine, low pressure compressor, low-pressure shaft, fan module, and combustion chamber structure. Whether IHI will eventually take on work in the “hot section” is uncertain. However, the broad trend is clear — consortium partners have been steadily increasing their share of engine programs.

IHI’s engine portfolio

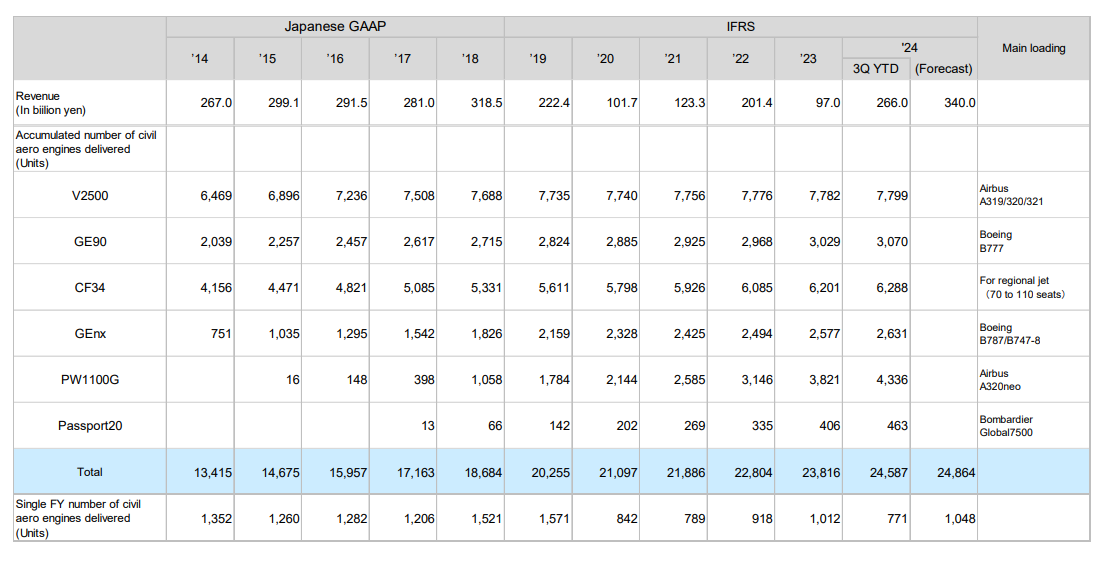

A good portfolio strikes the right balance between profitability and growth. Ideally, it should have mature platforms with established install base generating strong aftersales profit, while reinvesting into newer platforms that will secure future market share. IHI has a well-balanced portfolio, as shown below. The first generation platforms (V2500, CF34, GE90) are cash cows, while the second generation (PW1100Gand GEnx and Passport) are steadily ramping up. Its newest engine GE9X for the Boeing 777X will soon see its first commercial delivery.

Within the portfolio, the PW1100G deserves a special mention. It’s the flagship model of Pratt & Whitney’s breakthrough GTF (Geared Turbofan) family of engines for narrow-body aircrafts, powering the popular Airbus A320neo family.

The PW1100G competes directly with CFM’s LEAP engines, but the GTF is seen as the more innovative option, with P&W currently holding a monopoly on GTF technology. By employing a gear system that allows the fan and turbine to spin at different speeds, GTF technology can deliver up to 20% fuel savings and 75% reduced noise level thanks to optimal control of fan-speed.

How did P&W establish its position? P&W embarked on an entirely new innovation trajectory while CFM has opted to pursue incremental improvement on a conventional design. This is because GE’s core technology is unmatched in the industry, allowing CFM to keep pursuing incremental improvements without taking on too much risk. Seeing that it can never catch up to GE in the core technology, P&W embarked on a high-risk, high-reward path by betting on the novel GTF technology.

P&W’s bet seems to have paid off, with GTF engine earning widespread industry praise. And thanks to its new architecture, the GTF offers greater headroom for future enhancements than CFM’s LEAP, as this expert discusses.

“When you project within 10 or 15 years the LEAP, I think GE and Safran will really, really struggle to improve the LEAP because they have already put all of their best technologies in the engine. They have done this very well, by the way, but there is not really that much they can go after. They can still improve it a little bit, but they will struggle to find probably 4%, 5% more percent”

- Former Chief Commercial Officer at Airbus (November 2023, Alphasense)

However, the big issue with P&W is that it faced a major recall in recent years with the PW1100G engine (we’ll come back to this issue later, but for now let me just say that I think P&W can overcome this challenge).

Aftermarket growth (MRO)

For FY2023, IHI’s sales was split into:

Main unit (engine): 37%

Aftermarket: 63%

Spare parts: 58%

Maintenance, Repair, Overhaul (MRO): 5%

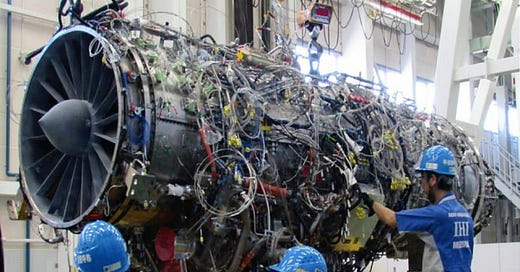

Until now, in a very Japanese fashion, IHI has focused on making the hardware (engine and spare parts) while being underexposed to servicing. However, this is about to change. IHI now wants to become a major player in MRO. CEO Ide has unveiled an ambitious plan to increase IHI’s maintenance capacity from 70 planes to 400, growing its MRO revenue from JPY 20 bn to 80bn. If you do the math, you will see that this is roughly 40% of the total growth of the civilian aero engine business.

I am bullish IHI’s growth in MRO, for several reasons.

MRO capacity shortage

Air traffic has only declined five times in the last five decades. It's grown over the last 20 years, anywhere from 3.7 to 7.5% air traffic growth p.a. according to Jeffries. As shown below, aftermarket growth rebounded after Covid and hit a peak in 2022 and 2023. While growth rate in 2024 has moderated, it is still above historical average. Note the figures in the chart below includes both spare parts and services. For services alone, the growth rate was actually 40% in 2024!

Several factors have contributed to the ongoing tightness in MRO:

During Covid, airliners deferred maintenance to cut costs, often swapping engines from idle aircraft to delay servicing. This created a massive backlog of deferred MRO work, which is still being cleared.

Structurally, many workers including mechanics left during the pandemic, and the resulting labor shortage has yet to fully recover (and may never?)

On the demand side, strong travel demand has kept flights consistently full.

First-generation engines like the CFM34 and GE90 (which require more frequent servicing to keep them operating) are being kept in service for longer, given the high travel demand and the slow delivery of new planes to replace them.

GTF as the growth driver

Over the coming years, more and more GTF engines will be past the five year mark, requiring more frequent and intensive shop visits including costly overhauls.

There’s also a new dynamic at play with the GTF engines. Engine OEMs typically build out their MRO network by granting overhaul licenses to third party shops, certifying them to perform work on the specific engine model. The key to note is that P&W seems to be pursuing a more “closed” MRO network for GTF engines than in the past (in contrast with CFM’s LEAP pursuing a more open model). Due to the novel design and complexity of the GTF engine, P&W has likely decided it wants to closely safeguard its trade secrets within its trusted network, thus relying more on its consortium partners to build out its MRO network.

If we look at GTF’s MRO network in Asia, the licensees are IHI, MHI, and MTU Zhuhai (which are all consortium partners), and three airlines: Korean Air, Air China, and China Air (P&W likely gave out the overhaul licenses to the airlines as a “sweetener” for the engine deals, which is a common practice in the industry). No independent MRO provider in Asia has been granted a GTF overhaul license. Compared to first generation engines where a long tail of third party MRO providers were part of the network, GTF’s network is more restricted to just the consortium partners.

Business development

Another big change we will see is IHI proactively pursing business development in MRO, compared to its more passive approach in the past. Until now, a large part of IHI’s business has been subcontracted work given by OEM (for OEM maintenance programs) or by other MRO shops when they want IHI to repair the components or modules they produced.

A true full-fledged MRO business goes beyond just taking on subcontracted work. If we look at MTU which operates the industry’s largest independent MRO, it’s much more than just repairing their own products. They’ve become a comprehensive provider, not only taking on subcontracted work but also independently go after and signing on their own customers including airlines and aircraft leasing companies, selling them comprehensive servicing packages.

MRO sales accounts for 66% of MTU’s total aerospace sales (i.e. 2x its manufacturing business including engine and spare parts). MRO sales includes reselling of third party components (as part of total servicing package), so it’s not just services revenue alone (it’s said that ~70% of MRO bill is material). That said, it gives you an idea of the scale of a full-fledged independent MRO business. While IHI will not reach MTU’s scale in MRO anytime soon, IHI’s current MRO sales at only 5% of revenue has significant room to grow from such a small base.

IHI has a key advantage in the MRO business as a consortium player that manufactures parts. By leveraging its spare parts business, IHI can effectively subsidize MRO growth, offering parts at cost to undercut other third party MROs. If IHI is truly committed to growing its MRO business, I think non-consortium players would struggle to compete.

I expect IHI to ramp up its business development focus on LCCs (low cost carriers). First, LCC fleets mainly consist of narrow-body jets and are thus major operators of GTF engines. Second, IHI has the opportunity to sign comprehensive servicing agreements with LCCs, as many lack in-house maintenance facilities, often relying on the facilities of larger airlines or independent MROs.

Industry cycle

Currently, both GE and P&W are seeing around 10-11k new engine orders and commitments for their LEAP and GTF engines respectively. With GE’s current delivery rate of around 1.4-1.5k engines per year, and P&W just under 1k, this is equivalent to 6 to 10 years of new engine backlog (note: Boeing and Airbus are averaging 14 years!)

The backlog continues to grow across both new engines and servicing: GE booked 50% commercial order growth in Q4 2024 with a book-to-bill ratio of 1.67 (1.35 in services and 2.47 in new engines).

Amid tightness, the industry has been turning to pricing increases. Rolls Royce is the most notorious for spearheading this, after its new charismatic CEO Mr. Tufan said he doesn’t believe airlines and OEMs are paying enough for the level of technology engine providers are providing. Rolls calls their new pricing strategy “value-driven pricing”. While Rolls has been the most vocal, others have also followed, with IHI reporting a pricing increase for the GEnx engine during its recent quarterly results.

Another very interesting observation comes from an industry veteran. Every company in civilian aerospace also has a defense business. When it comes to capacity, he thinks these firms will all prioritize the more lucrative defense side, possibly exacerbating the under-capacity on the civilian side.

“There is another issue that is playing out is I think it's in Europe and Japan and in Asia and in U.S., both North America. Defense spending hasn't slowed down…You know how long it takes to get paid when you are working on a defense contract? You have any idea? Two weeks. Yeah, two weeks. Yeah and it's a cost-plus. If MTU is producing a part and they just have to say, "Hey, my price went up by 12%." They can validate. Department of Defense will accept that, and they will write them a check. On the commercial side, if MTU says, "My price went up by 12%," all the different customers will be all over them and say why, this and that, and boom, boom. If I have a choice, where would I put my capacity? I will put it towards defense.”

- Former Director at Pratt & Whitney (May 2023, Alphasense Transcript)

More on the PW1100G recall

Contaminated powdered metal was found in the alloys of certain engine parts manufactured between Q4 2015 and Q3 2021, prompting a recall of around 3,000 engines. This resulted in major operational delays to airlines, as each engine required 250–300 days of overhaul to fix.

The issue affected the high-pressure turbine area, which is solely P&W’s responsibility and does not involve any of the consortium partners. However, losses are mutualized within the consortium. Total losses amounted to USD 7 bn including compensation to customers. Given its 15% program share, IHI took on roughly USD 1 bn in losses. All of this was written off in a single year in FY2024/3, and management expects no further financial impact.

Most importantly, what does this mean for the future of GTF?

P&W booked 950 GTF orders in 2024, compared to total engine shipment of 996. Book-to-bill should be around 1x (P&W doesn’t provide a breakdown but the vast majority of total shipment should be GTF)

Compared to LEAP’s book-to-bill of 2.14x, it does seem like some customers have been lost to GE.

Longer term I expect the GTF to make a comeback. First, based on expert calls, the industry still seems to recognize the technical advantage of the GTF and its long-term potential. Second, the current industry tightness makes it hard for customers to cancel additional orders. Third, the industry doesn’t want CFM to monopolize the narrow-body market, and thus should continue to support P&W.

What the recall revealed however was a flaw in the consortium model. Most high-risk developments occur in the engine’s “hot areas” which are handled by the OEMs. However, the risk is shared across consortium partners, leaving them vulnerable to the OEM’s faults despite having little control over these areas. While flawed, the consortium model isn’t expected to change however. Partners will just have to suck it up. Learning from this incident, IHI says that for its upcoming GE9X engine, they have “taken preventive measures based on our experience in this incident,” although specifics were not mentioned.

Thank you for reading. To be continued into Part 2…

![Urban dock LaLaport Toyosu (Tokyo, Japan) | [Official] MYSTAYS HOTEL GROUP Urban dock LaLaport Toyosu (Tokyo, Japan) | [Official] MYSTAYS HOTEL GROUP](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!EqMe!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F2bd2d9b5-a492-4c75-a322-ac54f2cd1b8e_940x580.jpeg)