Carlit Co Ltd (4275)

Niche monopoly defense player at 4.5x EV/EBIT

Disclaimer: The information in this article reflects the personal views of the author and is provided for informational purposes only. It should not be construed as investment advice. The author holds a position in the security at the time of publication. Investment funds or other entities with which the author has consulting or advisory relationships may or may not hold a position in the security/securities discussed. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect those of any other parties. Readers should conduct their own research and consult a qualified financial advisor before making any investment decisions.

Carlit is a small Japanese conglomerate that happens to control a critical chokepoint: it is Japan’s monopoly producer of ammonium perchlorate (AP), a key material that’s needed to produce missiles and rockets.

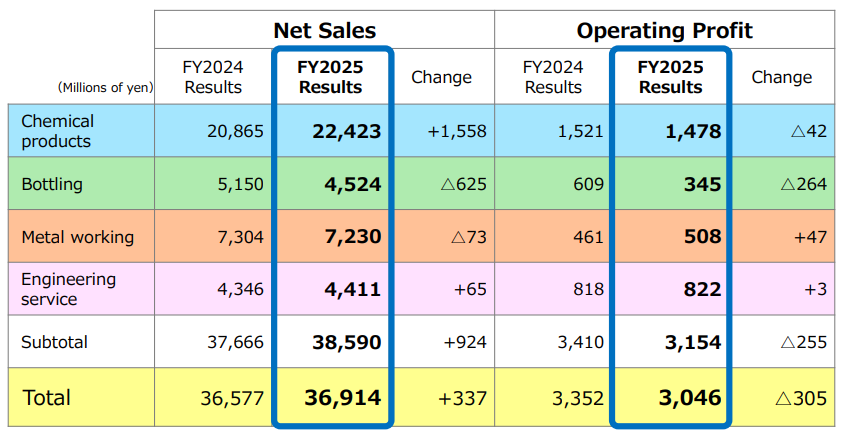

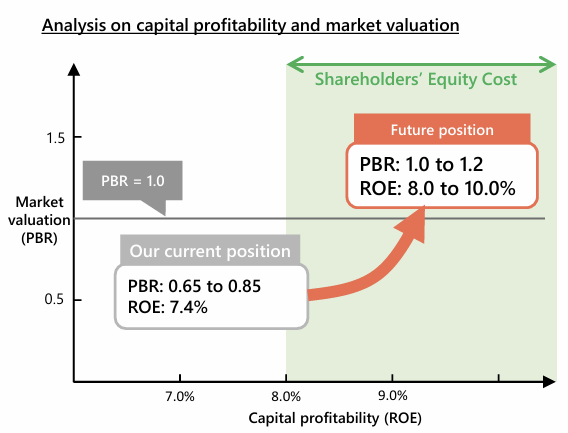

Carlit trades has a market cap of 32bn yen and has 4.5bn in net cash and 8.6bn of long-term investment securities. It trades at an EV/EBIT of 4.5x (FY27ce) or P/E of 10x (which becomes 6.3x after adjusting for net cash and investment securities). In today’s world, what do you think is an appropriate multiple for a monopoly defense player?

What is ammonium perchlorate (AP) and why it matters

Earth’s upper atmosphere and space contains little to no oxygen, so missiles and rockets have to carry their own source of oxygen for combustion. This is where AP comes in.

AP is an oxidizer, which means when ignited, it decomposes rapidly and “donates” oxygen to produce high-temperature combustion. It’s mixed with fuel, binders, and other chemical agents as part of the solid propellant for missiles and rockets. AP comprises 50-70% of the weight of the solid propellant.

There is no other oxidizer that can match AP’s combination of high performance, cost, and track record. AP has been used globally as the dominant oxidizer for the last seven decades. You can read about “green” oxidizers or other experimental alternatives in the labs today but for now, AP is irreplaceable.

Demand

Modern wars are increasingly fought with missiles, with boots on the ground reserved as a last resort. It’s worth noting that the current missile stockpiles maintained by countries around the world are essentially “peacetime stockpiles.” These levels are insufficient for a sustained conflict (as the recent Iran/Israel exchanges have clearly shown).

The trend is clear: countries are now scrambling to build more missiles. And among them, Japan stands out for having underinvested in this area. Japan is now playing catch up. Japan’s defense spending plans for FY2019–2023 vs.FY2023–2027 illustrate the scale of this shift:

The budget for “stand-off defense capabilities” will jump from 0.2 trillion yen to 5 trillion yen (a 25x increase!) This covers offensive missiles designed to strike enemy ground, sea, and air targets.

The budget for “integrated air and missile defense capabilities” will rise from 1 tn to 3 tn, which are defensive systems to intercept incoming missiles.

The budget for “cross-domain operation capabilities” will increase from 3 tn to 8 tn, which includes investments in the space domain.

Japan also plans to expand its space program, spanning both government and private-sector efforts. To support this, the government will revisit its space regulations, with new rules expected by 2026 in order to promote greater activity and increase private sector launches.

Carlit will be a direct beneficiary, since the company is Japan’s monopoly supplier of AP to both the defense and space programs (with defense expected to be the bigger contributor to growth). Currently, 100% of Carlit’s AP production is consumed domestically. Japan’s rising demand alone is absorbing all the capacity but in the future I think there could also be a market for exports.

Supply

Carlit is currently undergoing AP capacity expansion that will increase its total production by 2–3x. This expansion is demand-driven as outlined earlier.

Total investment is 2.5bn yen across three phases. Phase 1 is complete; Phase 2 will be complete in the first half of FY2026/3 (i.e. by September 2025); and Phase 3 is expected to be complete in the second half (i.e. by March 2026). Full operations are slated to begin from April 2026 onward.

The supply chain works as follows: Carlit produces AP and supplies it to NOF (4403), which blends the AP with other materials to manufacture solid propellant. NOF then delivers the solid propellant to IHI (I’ve covered IHI, see here for my deep-dive), which integrates it into a rocket motor, before supplying to final assemblers such as Mitsubishi Heavy Industries.

It’s also worth noting that NOF itself is undertaking a major capacity expansion for solid propellant, with completion timeline around September 2027. This means that while Carlit’s expansion will be finished by March 2026, there may be a lag before sales can fully ramp (depending on NOF’s current capacity, so the exact timing of the ramp remains somewhat uncertain).

The moat

The biggest question investors may have is why Carlit is the monopoly producer of AP (and whether this is sustainable).

Actually, Japan is not an exception. AP production in most countries around the world currently operate under a monopoly or duopoly structure.

United States: Duopoly in theory (American Pacific and Northrop Grumman) but in reality American Pacific dominates.

Japan: Monopoly (Carlit).

Continental Europe: Duopoly (French state-owned Eurenco and ArianeGroup, which is a JV between Airbus and Safran).

UK: Monopoly (Chemring).

Russia: Monopoly (state-owned ANOSIT).

India: Monopoly (state-owned APEP), although Solar Industries and Premier Explosives are trying to enter.

China: The only exception, with multiple SOEs producing AP.

Historically, there were more producers. For example, the U.S. had four producers during the Cold War. But decades of industry consolidation driven by defense budget cutbacks reduced the number of suppliers. Now that governments are scrambling to increase missile production, AP has emerged as a critical chokepoint. Every country wants more AP suppliers, but the challenge is that introducing new suppliers is easier said than done.

Why?

Producing AP is not hard, but AP from different suppliers may not be chemically identical. When it comes to something as sophisticated as ballistic missiles, even microscopic differences in the chemistry of AP can affect its ballistic curve (i.e. accuracy and performance). This means each weapons program has its own qualification process for a new supplier, and this often takes a lot of time and cost.

Ballistic missile launches cost millions of dollars for short-to-medium range missiles and tens of millions for long-range. Spending these amount only to validate AP, which costs only a few percentage of the total missile cost, makes little sense. Another reason qualification process takes time is due to the necessity of shelf-life testing. This is because missiles are designed to be stockpiled for decades, so degradation of AP over time is a key concern.

AP is also extremely hazardous in nature, and licenses and production sites are tightly regulated. The risks here are not just theoretical. In 1988, American Pacific suffered two massive explosions (measuring 3.0 and 3.5 on the Richter scale), resulting in two deaths, 372 injuries, and $100 million in damages to buildings within a 10-mile radius.

There is also the need for strict export controls, as AP is just white powder making it easy to smuggle. Its only real use case is in making extremely dangerous weapons. Governments strictly regulate exports and vet suppliers to prevent AP from falling into the wrong hands (terrorist groups, rogue states, etc.)

The conclusion is that producers with licensed facilities that already have their AP qualified and integrated into existing weapons programs enjoy a big moat. In fact, the barriers are so high that even with governments actively trying to diversify suppliers, new entrants have hard time breaking in. The US market serves as a great case study.

In the US, American Pacific (AMPAC) has been the monopoly AP producer, supplying the US government since the 1950s.

Northrop Grumman tried to enter recently. It built its first AP line in 2019–2020, scaled up in 2022, and received a generic qualification in 2021. On paper this created two suppliers, but progress has been slow. If you are interested, this is a good article on WSJ: “Northrop’s Rocket Fuel Factory Is Slow To Take Off”

As the author put it: “Years after building a factory to make more of the key chemical, Northrop’s output is still missing from the fuel powering many U.S. weapon systems.”

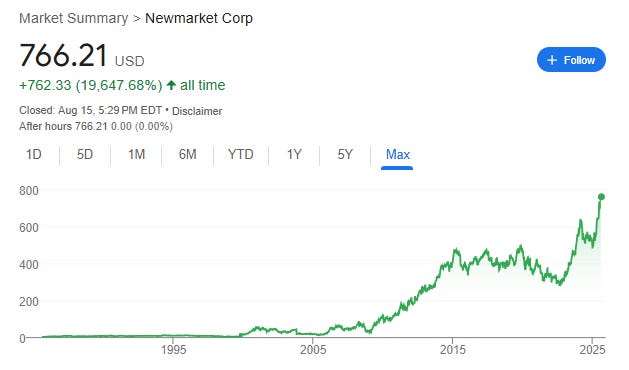

AMPAC itself has traded hands several times. The Huntsman family bought it in 2015, sold it to AE Industrial Partners (PE) in 2020, and in January 2024 it was acquired by publicly listed Newmarket Corp for $700mn.

Newmarket now reports AMPAC under its “Specialty Materials” segment. In FY2024 AMPAC delivered $141.2mn sales and $17.5mn in operating profit. The acquisition multiple was 40x forward operating profit.

Carlit

Vertically integrated producer of AP

Carlit also produces sodium chlorate and sodium perchlorate which are key inputs in the AP production process. These also have other industrial applications, in addition to their use in producing AP.

This vertical integration is another layer of moat for Carlit. For a second supplier to be cost competitive with Carlit, it would also need to internalize sodium chlorate production. But this may not be as easy as it sounds.

Case in point is Russia. According to one report, Russia has had no domestic production of sodium chlorate since the collapse of the USSR! As the article describes: “Ammonium perchlorate cannot be produced without sodium chlorate. Russia lost the ability to produce sodium chlorate domestically after the collapse of the USSR and remains dependent on imports, especially from China and Uzbekistan.”

Expanding upstream

Carlit is expanding beyond AP production into the design and production of solid propellant (in which AP is the key input) aiming to capture more value up the chain. The company has been supplying solid propellant to Japan’s space programs since 2017. But on the defense side (missiles), Carlit has so far only supplied AP. This is set to change, as Carlit is now investing 8bn yen to build solid propellant capabilities with plans for experimental mass production in 2027 and commercialization in 2028.

We know that Japan is advancing its indigenous missile capabilities. The timing of Carlit’s investment lines up with two key programs that are coming online soon and could feature Carlit’s solid propellant.

Hyper Velocity Gliding Projectile (HVGP): launched by a solid booster, with initial deployment scheduled for FY2026 (by Mar 2027). This is the most likely and most significant demand driver for Carlit’s solid propellant.

Upgraded Type-12 Surface-to-Ship Missile: first deployments pulled forward to FY2025 (by Mar 2026). These use solid boosters for launch but AP demand here is smaller relative to HVGP.

Looking further ahead, the Carlit’s TAM could also expand due to export opportunities. For example, China and Russia already exports AP to Iran. If allied nations face industrial bottlenecks or if conflict in Europe intensifies, Japan could very plausibly step in as a supplier of AP.

Estimating Carlit’s AP sales

Carlit’s management doesn’t disclose its exact AP sales but we can make a reasonable estimate as follows:

In April, AMPAC disclosed that it’s spending $100mn on its Utah expansion to add ~50% capacity. Its 2024 sales were $141mn which means $100mn capex added ~$70m annual sales.

Carlit is spending 2.5bn yen ($17m), which based on above should add ~1.75 bn of annual sales.

If this represents a 2-3x capacity increase, existing AP sales must be between 0.875 bn to 1.75 bn. Take the midpoint to get 1.3 bn, which represents 3.5% of Carlit’s consolidated sales, or 5.8% of the sales of the Chemical Products segment.

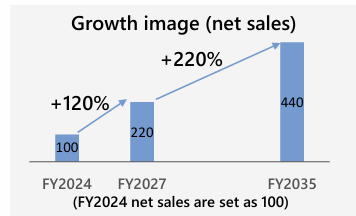

Carlit has provided guidance on its AP sales trajectory as shown below:

Carlit’s business portfolio

As shown earlier AP only accounts for a small portion of Carlit’s sales (although this is set to grow rapidly). Carlit is a diversified conglomerate with many businesses.

The company started as an explosives maker. Today, the chemical products segment includes not just AP but also industrial explosives, signal flares, and other products. These are mostly regulated, stable, and profitable businesses. Carlit also offers hazard assessment & testing which is a niche but attractive area. Because Carlit has long experience handling dangerous materials, it has built expertise in safety testing. This has become a profitable services business.

I’m not going to go through all of the businesses here but suffice to say that the company still operates many businesses that are shareholder value destructive. For example, there’s no reason why Carlit should be in the business of beverage bottling or producing silicon wafers. Management has not disclosed plans to divest these businesses but is instead focused on improving their profitability.

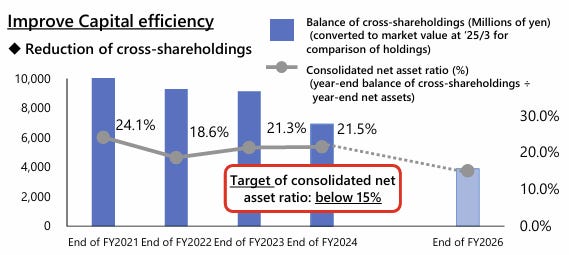

But governance has been improving. Carlit has been reducing cross-shareholdings, freeing up cash for shareholder returns. In May 2025, Carlit announced a major buyback program of 1.3mn shares (5.4% of outstanding). Dividend payout ratio has increased from 30% to 40% and management has explicitly stated it aims for PBR >1x.

Catalysts

Carlit’s AP capacity expansion will be done in March 2026. Management is guiding for profit growth, with FY2027/3 operating income forecasted at 4.2 bn yen, up from 3.1 bn in FY2026/3 and 3.05 bn in FY2025/3.

Japan announcing extra spending on defense and space programs. The Japanese government has been turning more right-wing and this could be further tailwind for defense spending.

Large-cap defense names like MHI, IHI, and KHI have already re-rated sharply. Even a small spillover of capital into names like Carlit could make its valuation skyrocket.

Publicly listed peers have done well. Newmarket (AMPAC’s parent), Chemring, and NOF’s shares have all surged recently. Is it Carlit’s turn?

Potential take-private: Carlit’s small market cap stands in stark contrast to its strategic importance as Japan’s sole AP producer. In fact it’s hard to think of another publicly listed company this small that plays such a critical role in national defense. Hence, this raises the question: is Carlit too strategic to remain listed? One possible scenario is that the Japanese government pressures a larger defense company (NOF being the most logical candidate) to acquire Carlit and delist it.

Risks:

Operational and natural disaster risk: an AP facility explosion would be catastrophic. The probability is very small but the outcome could be devastating. It’s worth keeping this in mind when sizing the position (this is more a reminder to myself since Carlit is now my largest position).

Carlit’s growth is partly tied to Japan’s space ambitions. Any major setbacks to Japan’s current space program (e.g. if the next few launches of the new H3 rocket ends as failures) would weight on future space-related demand.

Rotation away from defense names: Defense is a crowded trade. Any “permanent” ceasefire (Gaza/Israel, Ukraine/Russia) could lead to rotation out of defense names, until the next major conflict reignites investor interest.

Alternative technology: There is no immediate threat, but the possibility of a superior material replacing AP in the future cannot be fully ruled out.

Disclosure: The author holds shares of Carlit at the time of publication and may choose to sell these shares at any time without notice. This article does not constitute investment advice. Please refer to the disclaimer at the beginning of this article, and always conduct your own due diligence before making any investment decisions.

Fantastic write-up & name, unparalleled risk/reward ratio opportunity.