Every time I visit Tokyo, one of my favorite pastimes is visiting bookstores in the city's business district. The "featured books" section always offers an interesting glimpse into the prevailing narratives and mindset of the Japanese salaryman.

When I visited in early March, the prevailing theme seemed to be “change.” I saw many books that discuss the transformation of Japan’s old-economy companies, like Hitachi and Sony. There was a sense of optimism and hope.

This is a sharp contrast to a few years back, when I remember shelves being dominated by titles like The Japanese Economy: A Ticking Time Bomb, The Death of Japanese Manufacturing, and What Can We Learn from Alibaba and Tencent.

This time, one of the books I picked up was The Rebirth of Nippon Steel, which details the turnaround at Japan’s largest steelmaker.

The steelmaking industry might not seem interesting to everyone, but it’s an intriguing case study of how even the most old-fashioned and traditional industry in Japan can change. The book’s author persuasively argues that if a company as averse to change as Nippon Steel can do it, then there is perhaps hope for all Japanese firms.

So, what did the transformation at Nippon Steel entail? This article draws on the case study of Nippon Steel to examine the more broader topic of “change” in Japanese management.

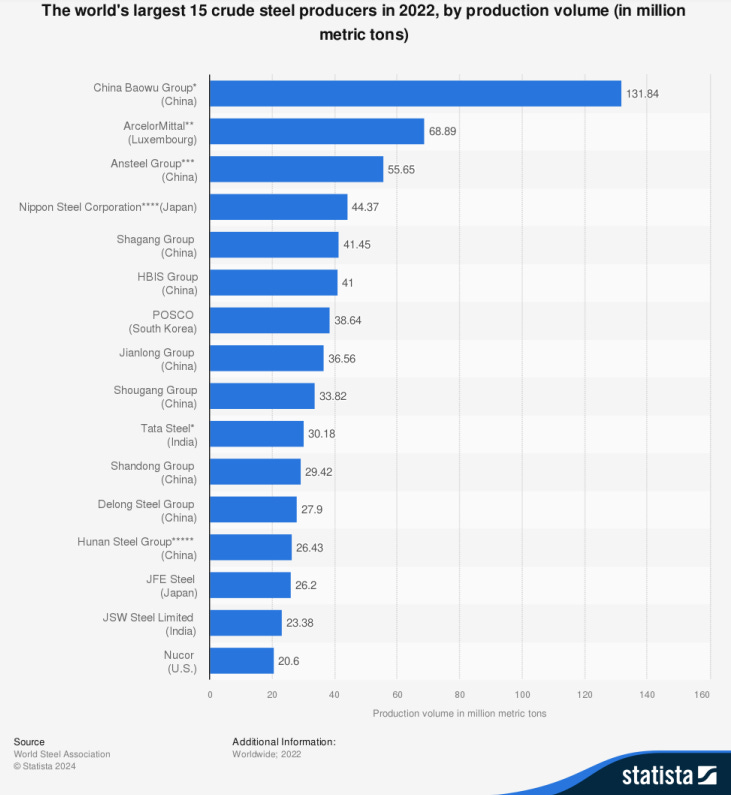

Nippon Steel is Japan’s largest steelmaker, formed from the 2012 mega-merger between Shin Nippon Steel and Sumitomo Metal. It has 50% market share of crude steel production in Japan, and ranks as the fourth largest steelmaker globally.

Japan’s steelmaking industry has undergone consolidation, due to increasing competitive threats from ArcelorMittal and the rise of Chinese and South Korean steelmakers. However, following the 2012 merger between Shin Nippon Steel and Sumitomo Metal, little had been done in restructuring the combined entity. There was no clear vision or strategy, and the organization was bloated and in disarray.

Meanwhile, volume was declining every year due to the slump in Japan’s domestic steel demand. The company also faced intense competition overseas. Over ten years, production volume declined by 20%. In a high operating leverage business like steelmaking, this kind of volume decline can be fatal. The company recorded negative profits for three consecutive years from March 2018 to March 2020.

Leadership Change

64-year-old Eiji Hashimoto became CEO in 2019, tasked with turning around Nippon Steel.

In my experience, Japanese turnarounds involving “Salaryman CEOs”, like in this case, can be subtle and hard to spot. This is because:

These CEOs often rise from within the ranks, rather than being experts brought from the outside. They can be company lifers, as is the case with Eiji Hashimoto. At first glance, they don’t seem all that different from their predecessors.

As a result, they also don’t have a “track record.”

Japanese CEOs are underpaid. The portion of their compensation which is tied to performance is very small relative to US and European CEOs. “What incentives do they have?” is the question investors might ask.

If American corporate turnarounds are like this:

Then Japanese “salaryman CEO” turnarounds are like this:

And when you underestimate the salaryman CEO, this is what happens.

When a guy like this comes along, it can unlock a lot of value for shareholders. Salaryman CEO turnarounds are underappreciated.

Eiji Hashimoto stands out as an unconventional leader. He obtained his Master’s degree from the Harvard Kennedy School, and was known for his “insubordination” at the workplace. In earlier years, his unwillingness to conform to traditional Japanese business approaches while working as a salesperson in Japan led to a fractured relationship with his boss. This led to Hashimoto being “sidelined” to Nippon Steel’s overseas businesses, where he would become involved in the company’s operations in Asia, the US, and Brazil.

A characteristic of these reform-minded salaryman CEOs is that they have quietly risen through the ranks, driven by a dissatisfaction with the status quo. They have a strong sense of mission to drive change, which can be unrelated to personal financial gains.

What did it take to turn around Nippon Steel? I will discuss four key points.

Dealing away with antiquated Japanese business practices

Reclaiming bargaining power with large clients

Headcount reduction

M&A and growth investments